From afar came merchant-men,

Bringing, on tidings of this birth, rich gifts

In golden trays; goat-shawls, and nard and jade . . . Waist-cloths sewn thick with pearls, and sandal-wood…

Victorian-era poets who flirted with Buddhism were enchanted by the parallels they discovered between the Christian nativity and legends about the Buddha’s past lives. The lines above come from Edwin Arnold’s long-form poem The Light of Asia (1879), about the life of the historical Buddha. It rivalled Mark Twain’s Adventures of Huckleberry Finn for sales and did a huge amount to popularise Buddhism across the West.

A century later, Japanese Zen had become by far the best-known form of Buddhism in the western world. Japan’s more theistic forms of Buddhism were less attractive to westerners because they looked too much like the Judaeo-Christian traditions that a great many of those westerners were seeking to escape. That seems a pity because some of the ideas and practices in sects like Jōdo Shinshū (‘True Pure Land’) shine an interesting light on western culture.

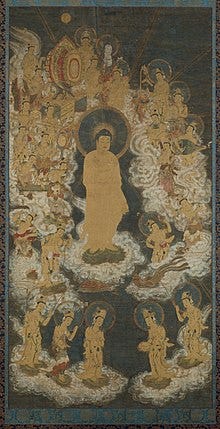

I’ve been thinking about this in recent weeks because as part of one of the courses I teach at Edinburgh University we explore the relationship between culture and mental health. Towards the end of the semester, we looked at a Japanese form of psychotherapy called Naikan - the word means ‘inner seeing’ or ‘inner reflection’. It has roots in a Jōdo Shinshū practice called mishirabe: a person would lock themselves up in a temple for long days of introspection until Amida Buddha granted them a flash of certain knowledge that they were saved - that upon death he would whisk them away to his paradisiacal Pure Land.

In the early part of the twentieth century, a handful of Japanese psychiatrists and psychotherapists began creating new therapies to help people cope with the stresses and strains of modern life. All of them drew, in some way, on Buddhist insights about suffering and a man called Yoshimoto Ishin borrowed in particular from mishirabe.

The form of therapy Yoshimoto created, in the 1940s, was entirely secular in its approach but started from the very basic Buddhist idea - familiar, too, in Christianity - that who we are as human beings is fundamentally a product of our relationships.

Naikan therapy happens via a retreat of sorts. Clients stay at a Naikan centre and their days are spent behind a screen in focused introspection. Their guide visits them now and again, asking them to focus on a particular relationship - their mother or father, for example - and apply to it three questions: What have I received from this person? What have I given to them? What trouble and difficulties have I caused them?

I always enjoy introducing Naikan to my students because almost always the response is that they would find it anything but therapeutic. It seems guaranteed instead to elicit powerful feelings of guilt - and surely in therapy we’re trying to go easier on ourselves?

Guilt is no doubt an early product of Naikan therapy, especially if you’ve been brought up in a strongly individualistic culture: the default idea is that anything you do in life is ‘yours’ - you chose it; you’re responsible for it. Buddhism takes a different view, and Naikan helps clients to really see and feel it. Looking back at your relationship with, say, your mother, and meditating on these three questions is not intended to burden you with thoughts of what a terrible and ungrateful daughter or son you’ve been. It shows you just how deeply you’ve been shaped by that relationship.

The insight here is not merely that we’re all profoundly influenced by our relationships, but that in some sense we are our relationships. You could take that in a social or psychological sense: our sense of ourselves relies on how others have nurtured, taught and responded to us, right down to our basic emotional patterns and our ability to use language. Or you could go a step further and argue, as some do, that whether via a Buddhist network of cause-and-effect or a Christian notion of love flowing within and between people, relationships are as real or even more real than the people involved in them.

There are darker sides to this idea, of course. After the end of World War II, there were those in Japan who argued that an underdeveloped sense of individualism in their country had made it possible for political and military leaders to force people into a catastrophic conflict. Critics of contemporary Japan - both Japanese and non-Japanese - will tell you that the importance of relationships is a value easily weaponised by people making unreasonable demands of you, from overbearing bosses to domineering family members.

Still, I’m glad to have Naikan on my mind as we head into Christmas. ‘Good will to all’ feels like a richer proposition when accompanied by a little reflection on how much various people in my life have given to me, nurtured and shaped me. Even if it happens not in the austere surrounds of a Buddhist temple or a Naikan centre but instead in a haze of drink, chocolate and the Strictly Come Dancing Christmas special, it’ll be wonderful nonetheless.

Wishing you and your loved ones a happy and peaceful Christmas, and see you in the new year.