I Need a (Japanese) Hero...

Flicking through the Japan options on Netflix - in search of spousal overlap for some evening viewing - I was struck by the images of Japanese heroism on offer. There seemed to be basically three, all linked in some way to World War II and its aftermath.

First off, and maybe the most obvious: samurai. There are documentaries (Age of Samurai), manga adaptations (Rurouni Kenshin) and the slightly strange Samurai Gourmet, about a salaryman seeking purpose in life after retirement (my view: nothing much happens. My wife’s view: nothing much happens - and that’s great).

Samurai Gourmet (2017)

In the years after WWII, officials in Japan whose job it was to promote their country abroad wouldn’t touch the samurai with a bargepole. Flower-arranging, the tea ceremony, images of temples and shrines? All fine. A reminder of Japan’s martial tradition, disastrously adopted and twisted by mid-century militarists? Absolutely not.

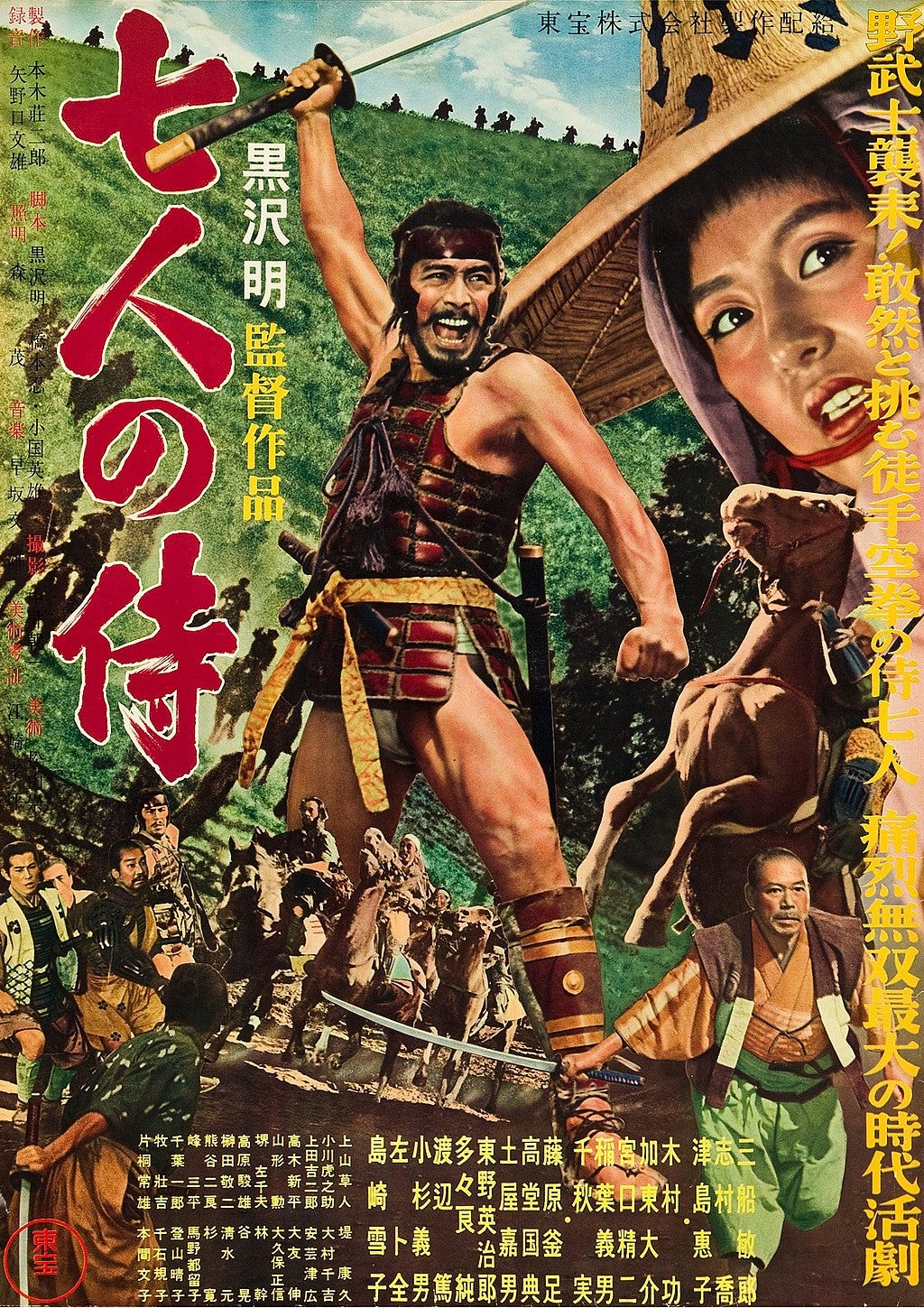

Outside Japan, the film director Akira Kurosawa and his leading man Toshiro Mifune did much to kindle a sympathetic western interest in the samurai. Seven Samurai (1954), about a group of farmers who hire a masterless samurai (rōnin) to defend them against bandits, was one of his most celebrated films.

Inside Japan - where Kurosawa never had quite the same status as abroad - the return to popularity of the samurai owed a great deal to people’s love of historical drama (film, theatre, novels, manga).

Many Japanese were keen to see the events of the 1930s and ‘40s as a terrible interlude in a much longer and more benign history. Samurai films were capable of transporting them back into the past, and evoking a form of heroism rooted in the warrior code (bushidō): honour, loyalty, defending the vulnerable.

These films also captured the swagger, earthy charm and subversiveness associated with rōnin in particular - entertaining in itself, and a great way to contribute to debates about how, in light of the recent war, to balance virtues like trust and loyalty with a willingness to resist corrupt leaders and institutions.

Seven Samurai (1954)

The second kind of heroism that you’ll find on Netflix comes courtesy of the yakuza, Japan’s old-school gangsters.

The word yakuza comes from a losing hand in a card game – ya (8), ku (9), za (3) – and some of the earliest, centuries ago, were pedlars and gamblers. They might try to sell you a fake bonsai tree or some medicine that didn’t work, or you might see them pass by on the road wearing cape, sword and sedge hat.

Twentieth-century yakuza got up to all sorts. They were employed to break strikes. They could be hired to attack or defend politicians. And in the aftermath of World War II, some of them ran black markets and bankrolled early postwar politics.

None of this would necessarily endear the yakuza to people, whether in Japan or beyond. But like the samurai, they were associated - by supporters, at least - not just with violence but also with a code of honour and a willingness to stick up for the little guy (yakuza sometimes used the term ‘chivalrous organisation’ to describe themselves).

For a certain kind of critic who worried that Japan was becoming too westernized across the twentieth century, or too much a ‘me-first’ society, the yakuza could be defended as ‘corrupt’ only in the limited, business sense of that word. In cultural terms, so the argument went, they represented tradition and collective values. In one scene from Informa, a yakuza drama that came to Netflix earlier this year, a gangster boss declares with great emotion to his underling that he must ‘protect Japan’.

Informa (2023)

The final kind of Japanese heroism to be found on Netflix comes in the form of Studio Ghibli animations. One of the lessons that animators of Miyazaki Hayao’s generation took from the war was that children ought to be offered a realistic sense of the adult world: deeply flawed, and easily infected by dangerous ideas. Children were mature enough to handle a degree of exposure to this world, thought the likes of Miyazaki and Tezuka Osamu (‘godfather of Japanese manga’). And it might help to avoid disaster in the future.

Alongside this willingness to blend the child and adult worlds - key to the success of Ghibli in the West - was a form of heroism that Ghibli fans all around the world will readily recognise. Whether it is Nausicaä in Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind (1984) or Chihiro, in Spirited Away (2001), hostile forces are won over or pushed back by kindness, compassion and a deep empathy for other people’s plights and points of view.

Miyazaki doesn’t preach. He shows his audiences that these values are forces for good not just on a moral level but on a metaphysical one, too: goodness is what brings the world into being, from the flourishing - and restoration - of nature to real relationships between people.

Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind (1984)

It’s wonderful that the Ghibli films are more readily available now than ever. But there is another Japanese hero, from this same postwar tradition, whose time has surely come to step out of the shadows…

He is all but unknown in the West. And yet if you live in Japan - especially if you have children, or were a child yourself within living memory - you cannot possibly have avoided him: Anpanman.

Anpanman is a caped superhero, whose head is a bean-paste bun. This has its downsides. Where Superman’s nemesis substance is kryptonite, not readily obtainable by his enemies, Anpanman’s is troublingly ubiquitous: water. A quick squirt from a water-cannon – at whose controls his arch-enemy Baikinman (Germ Man) sits cackling his dastardly cackle – and Anpanman is done for. He falls out of the sky, and has to be rescued by those he was trying to save.

Anpanman’s creator, Yanase Takashi, served in China towards the end of World War II. The experience turned him into an ardent pacifist, forever suspicious of traditional forms of Japanese heroism and their co-option by Japan’s militarists. A true hero, Yanase decided, shows compassion and is concerned above all with feeding the hungry.

To that end, one of Anpanman’s trademark moves - slightly unnerving to anyone seeing it for the first time - is to tear off a chunk of his head and give it to someone in need. ‘Please, never write something like this again’, commented the mother of an early Anpanman reader.

Precisely fifty years on from that first manga, back in 1973, Anpanman has thoroughly conquered Japan - via anime series, films, toothpastes, bedspreads, lunchboxes and much, much more. Generations of children have grown up with his innocent, naive charm. And generations of parents have sat - umpteen times - through the famously upbeat ‘Anpanman March’:

Maybe Anpanman would be a little too left-field for western audiences, with his array of friends based on tasty foods brought to life - Katsudon-man, Currypan-man.

But if you find yourself holding out for a hero, you could do a lot worse than this one.

Anpanman and Baikinman

—

Suggested reading:

Donald Richie, A Hundred Years of Japanese Film (Kodansha America, 2012)

Eiko Maruko Siniawer, Ruffians, Yakuza, Nationalists: The Violent Politics of Modern Japan, 1860–1960 (Cornell University Press, 2008)

Thomas Conlan (ed/trans), Samurai and the Warrior Culture of Japan, 471–1877: A Sourcebook (Hackett Publishing, 2022)

Oleg Benesch, Inventing the Way of the Samurai (Oxford University Press, 2016)

Michael Leader & Jake Cunningham, Ghibliotheque: The Unofficial Guide to the Movies of Studio Ghibli (Welbeck, 2021)

—

Images:

Samurai Gourmet: Gokodama (fair use).

Seven Samurai: Creative Common (public domain).

Informa: Netflix (fair use).

Nausicaä: Barbican (fair use).

Anpanman: Fandom (fair use).

Baikinman: Fandom (fair use).

Anpanman March: YouTube (fair use).