* SPOILER ALERT: contains minor spoilers for The Boy and the Heron *

Last week, I went to see The Boy and the Heron with my teenage son. We had wanted to see it anyway, but a request came in to discuss it with Alastair Benn on the Engelsberg Ideas podcast, and that provided the final push.

So along we went, both of us Japanese-speakers but making do with the dubbed version on offer at our nearest cinema. I prefer original language versions where possible, not (I hope!) because I’m a tiresome film purist but because there’s something jarring about the attributing of English voices with varying accents to Japanese characters.

I find myself wondering why this character has been given a vaguely cockney accent, or that one a southern American drawl. What are they trying to tell me with those choices? What am I supposed to take away?

An hour into the film, and this was the least of my troubles. I was completely lost.

For the first forty minutes, Miyazaki had me firmly in his grasp. A young boy, Mahito, loses his mother to a fire during World War II. Mahito has an awful, wrenching sense of having failed to save her - even though neither the fire nor the failed rescue were his fault.

Mahito and his father relocate to the countryside, where the father runs a company manufacturing aircraft for the war effort. With what my son noted was a disappointingly rapid turnaround time, the father gets married again: to the sister of his deceased wife.

All this is beautifully done, with a lush rural setting and the pathos of seeing Mahito try to adapt to a new life - school bullies included - whilst grieving his mother.

At one point, it all becomes too much and Mahito smashes a rock into the side of his head. He ends up bed-bound, being fussed over by a gaggle of old ladies in kimono, one of whom is a little reminiscent of Yubaba in Spirited Away.

The film becomes ever more dream-like thereafter: we are plunged into an oceanic world; we meet an old wizard in a tower; we find dolls becoming humans and humans becoming dolls.

When the action at last returns to Mahito’s everyday existence, the story seems to wrap up very quickly. As far as it’s possible to sense bewilderment in a cinema, that’s what my son and I sensed, when the lights came up and we all began filing quietly out.

My podcast interview was scheduled for the following day, and I wasn’t at all sure what I was going to say. My son and I puzzled it through on the way home – a joy in itself, but yielding few results with which I might justify my existence to the audience for Engelsberg Ideas.

I wondered – sacrilege though it is to suggest – whether some of the positive reviews for The Boy and the Heron had about them an element of The Emperor’s New Clothes. This is expected to be Miyazaki’s last film (though he has ‘retired’ on many occasions), and so a phrase like ‘late masterpiece’ trips easily off the tongue. My wife noted that there have been fewer reviews in the Japanese media than one might have expected. Were editors and journalists in Japan opting for dignified silence over insult to a cultural icon?

To my rescue rode Alastair Benn, Deputy Editor at Engelsberg Ideas.

The film, Benn said, had deeply affected him (this made me feel a little hard-hearted: I had all but drifted off to sleep in a couple of places). Benn found that Miyazaki had somehow managed to conjure sequences that he recognised from his own dreams. What’s more, symbols were everywhere in that long, dream-like portion of the film – for those who’d had enough sleep the night before to pay proper attention.

I found all this quite persuasive. Most of the Miyazaki films that I’ve seen have steered me along quite nicely: visually-exhilarating journeys, set to music by the legendary Joe Hisaishi, in which I know more or less where I am the whole time. Not so The Boy and the Heron. It seems to ask much more of viewers than Miyazaki’s earlier films did - and I hadn’t been expecting to give it.

If I get the chance, I’ll go to see the film again, both because I’d like to test it out in Japanese and because I suspect that what I experienced as a slightly incoherent story may instead be a freewheeling, go-where-it-must study of grief, and a probing of the recesses of viewers’ imaginations.

All that said…

Were I to indulge in a little of what my wife calls iiwake kusai - ‘stinking of excuses’ - I might add that the choice of English title for the film didn’t help viewers out very much.

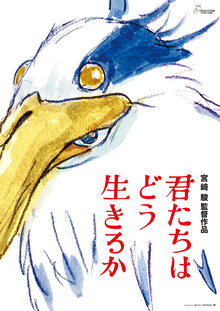

The Japanese title is Kimitachi wa dō ikiruka: How Do You [plural] Live? This surely prepares viewers better for what is about to be asked of them. And it chimes with a lovely moment towards the end of the film, when the wizard looks on as a tower built from a stack of three-dimensional shapes – pyramids, spheres, etc – wobbles precariously in front of him. For many years, he has just about kept it from toppling. But it’s clear, now, that that moment cannot be far away.

The precariousness of the world as human beings have constructed it has been a deep concern for Miyazaki right across his long career. Here, perhaps, is his sign-off. The wizard turns to Mahito, and asks: ‘How would you build this?

Thanks for reading! You can listen to my chat with Alastair Benn HERE. Please also consider subscribing to IlluminAsia if you haven’t yet done so…

… and perhaps sharing this post if you know someone who might like it.

—

Images:

Studio Ghibli, from The Boy and the Heron (fair use).

I too felt bewildered and honestly confused at the end of the movie. Even I who considers himself an artsy film-snob, I didn't know how to feel. I am happy you were able to, at least partly, put my feelings into writing.

https://perennialdigression.substack.com/p/zephyr-v

For what it’s worth, and only if it helps, I wrote a review unpacking some of the themes here.