There’s an episode in Blackadder the Third featuring a fabulously verbose Samuel Johnson, played by Robbie Coltrane, at the point where he’s just finished compiling his great dictionary. The book has taken him ten years and it contains, he says, ‘every word in our beloved English language’.

Blackadder starts to taunt him – ‘every single word?’ – firing off made-up bits of nonsense that a flustered Johnson hurriedly scribbles onto his manuscript

Without pretending to compare myself to Johnson, I can understand how he might have felt. In The Light of Asia, I wanted to give readers a flavour of western interest in ‘the East,’ down the centuries. But there is so much to say, and as time goes on I keep thinking of people and episodes I left out.

So after a little while away from IlluminAsia, working on A Short History of Japan plus a few other things (fans of The White Lotus might be interested in this), I’m re-starting my monthly essays with a short series featuring parts of the East-West encounter that didn’t make it into The Light of Asia. Not because they didn’t deserve to - this isn’t ‘bonus material’ of the dubiously substandard sort. It’s more because either they didn’t occur to me in time or there wasn’t space for them in the book.

Later in the year, I’m going to take up the theme of desire. A great deal of western interest in Asian spiritualities over the past century has focused on the austere and the self-denying, from the rigours of Zen to the physical disciplines of yoga. The self-help mentality that has fed our interest in Asia has played a role here, I think. Until relatively recently, it has been largely about discerning negative habits or patterns of thought and trying to do away with them.

Put it down to a succession of failed diets and soon-forgotten New Year’s grand plans, but I’m more interested now in how we might work with our desires rather than disown them. Asian traditions have a lot to say about this, not least India’s bhakti movement – which is all about cutting loose with love and devotion. As always, if there’s anything you’d like me to cover on IlluminAsia, please feel free to drop me a line.

So. Nazis. For all the ‘light’ that Asia has shone into western life, our fascination with Asia has had its darker sides, too. An example of this that did make it into The Light of Asia was the way that British exploration of Indian spirituality was undertaken in part as a means of ruling India more efficiently. As Governor-General Warren Hastings put it, in a prefatory letter for the first English translation of the Bhagavad Gita in 1785: ‘every accumulation of knowledge is useful to the state.’

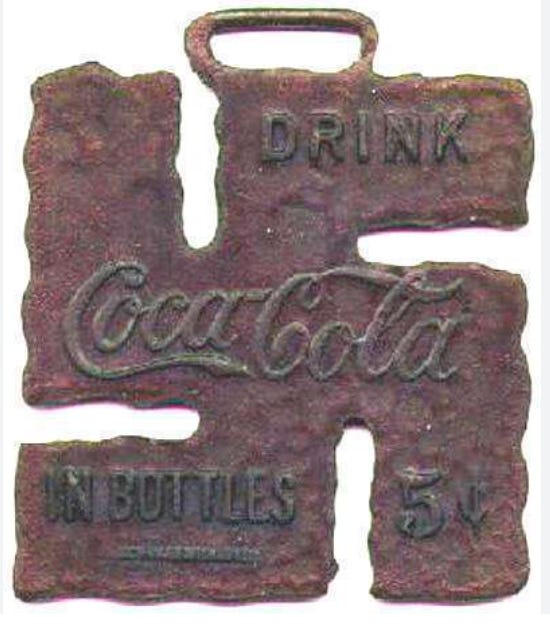

Darker still was Nazi interest in Asia. The most obvious example is their adoption of the ancient swastika symbol, widely used in religious traditions in India and elsewhere in the world – the word itself comes from the Sanskrit word swasti, meaning ‘well’ and ‘good.’ It’s worth noting that plenty of other unlikely organisations used the symbol before the Nazis got to it, from American military units in World War One to Coca-Cola:

Beyond the swastika, the Nazis were heirs to decades of German interest in Asia, from painters and poets to linguists and spiritual seekers. They inherited, too, a range of mystical musings on places like Tibet, which cast remote and as-yet minimally explored parts of the world as lands of mystery and magic.

Madame Blavatsky did much to power this trend. She was a charismatic and highly influential figure in the Theosophy movement, one of many attempts in the late 19th and early 20th centuries to combine science, spiritual wisdom, myth and magic. Asian religious traditions like Hinduism and Buddhism were often looked to, with great hope, as sources of inspiration for achieving such a synthesis.

For all her brilliance, Blavatsky had a weakness for the tall tale. She claimed – falsely, it seems - to have travelled to Tibet, and to have met spiritual masters there with whom she later communicated via telepathic means. She also picked up on Tibetan Buddhist ideas about a place of great spiritual significance called Shambhala. Passing via James Hilton’s 1933 novel Lost Horizon, it became ‘Shangri-La’: an imaginary place entirely devoted to wisdom, where one may live forever.

Madame Blavatsky

There has been much debate about just how interested top Nazis really were in Asia and in the occult. Eric Kurlander’s Hitler’s Monsters (2018) is well worth a read on this. He argues that the Nazis made serious use of what he calls a ‘supernatural imaginary’ at various points across the 1930s and 1940s, drawing broadly on Asian religions and mythologies alongside Europe’s own past.

In a striking parallel with wartime Japan, members of the Nazi hierarchy fantasised about creating miracle weapons, some of them inspired by esoteric ideas, which would be capable of turning the tide of the war in their favour. Japanese writers imagined shooting a beam of energy from a mountain cave somewhere in Japan and Washington DC exploding in flames seconds later. The Nazis hoped to produce ‘death rays’ of their own, capable of downing enemy aircraft. But Heinrich Himmler was amongst those who placed their faith in ‘paranormal powers and extraordinary weapons,’ the latter harnessing as-yet undiscovered forces in the universe. Attempts were even made to use divination to consolidate Nazi power.

The place of Asia in all this was as a source of fresh wisdom, both mystical and scientific, and as home to members of a putative, long-since dispersed Aryan race - an important Nazi myth, rooted in linguistic theories from earlier decades. Some thought that superhuman powers might reside, dormant, in this Aryan race and that to unlock them the Nazis - as contemporary defenders of that race - needed to find an example of true racial purity in a place where marriage outside of the group had been vanishingly rare across long stretches of time. Tibet, they hoped, was one such place.

Nazi theorists hoping to keep Himmler happy put together the rudiments of a racial theory linking the Aryan race to Tibet, drawing in part as they did so on Madame Blavatsky’s writings about the country. Some also hoped to find in Tibet a form of alternative science, an ‘Aryan physics,’ which might furnish a fresh theory of relativity – countering the one offered by the unacceptably Jewish Albert Einstein.

To these eccentric ends, and hoping to undermine Britain’s strategic position in South Asia, Himmler sponsored a German expedition to Tibet in 1938-9. It was led by five academics who were all given SS ranks and required to wear SS uniforms. Protestations were made about Germany and Tibet being close spiritual and racial relations, and the expedition being a great meeting of East and West.

Members of the expedition in Tibet

Not all of the expedition’s participants were fully signed up to Himmler’s Tibetan fantasy. Ernst Schäfer was more interested in tracking down the famous ‘giant panda’ and the team as a whole succeeded more in gathering a rich haul of information about Tibetan peoples, flora and fauna than in locating the lost remnants of a master race. They took photos, made cranial measurements and facial casts of some of the people they encountered, and when they returned home they brought with them seeds, butterflies and animal skins.

Himmler is said to have met the expedition at the airport in Munich, upon their return. You have to wonder what they told him – he was not, after all, a man who liked to be let down. No doubt the failure of the Tibetan expedition to provide the Nazis with magical powers was disappointing to him, but the romance and propaganda potential remained of the ancient, the exotic and the unknown.

The mid-twentieth century marriage of religious romanticism with extreme politics has occasionally made life difficult for those who want to critique western secular modernity by extolling the virtues of ancient and/or Asian alternatives. Zen Buddhism has struggled with the legacy of its co-operation with Japanese ultra-nationalism. Westerners drawn to Hinduism and yoga have to contend with their role in India’s chauvinistic ‘Hindutva’ politics, which marginalises Muslims, Sikhs, Christians and members of other religious traditions.

Thankfully, generations of postwar scholars and spiritual seekers have made it possible for us to take a more nuanced, more hopeful approach. Recently, I’ve been reading the autobiography of one of those scholars, Huston Smith, who rather than making brief, deluded expeditions spent many years studying Hinduism in India and Zen in Japan - he’s someone else I would like to have featured in The Light of Asia. I’ll end on a few lines from him, offering his view of life after death following a career spent exploring religious traditions from around the world:

After I shed my body, I will continue to be conscious of the life I have lived and the people who remain on earth. Sooner or later, however, there will come a time when no one alive will have heard of Huston Smith, let alone have known him, whereupon there ceases to be any point in my hanging around… I will then turn my back on planet earth and attend to what is more interesting, the beatific vision.

After oscillating back and forth between enjoying the sunset and enjoying Huston-Smith-enjoying-the-sunset, I expect to find the uncompromised sunset more absorbing. The string will have been cut. The bird will be free.