Today is one of the biggest days in the Christian calendar: Good Friday, commemorating the death of Jesus of Nazareth almost two thousand years ago.

Depending on your perspective, it was an act of judicial murder, an ignominious end to a radical teaching career, an extraordinary gesture of love or a grand cosmic moment when a mysterious act of sacrifice placed God and mankind into a new and better relationship. For some, no doubt, it was a little of all these things.

It’s a bit beyond my pay-grade to propose an answer, but instead this seems like a good moment to take up the theme of sacrifice, as it has played out in Japan down the centuries. I’m going to explore the rise, fall and final perversion of sacrifice as an ideal - across two posts, this week and next.

Work seems to have been wall-to-wall samurai of late. I’ve started writing my next book, Barbarians, which explores the first century of contact between Europe and Japan in the turbulent 16th and early 17th centuries. And I’ve done a few interviews about the samurai, including a podcast with Dan Snow and a couple of television conversations: one for the BBC, on Edo Japan, and the other for a forthcoming series about World War II, set to be narrated by the one and only Tom Hanks.

One of the topics for the WWII interview was the Battle of Okinawa, which raged eighty years ago this month and was famous - infamous, perhaps - for Japan’s heavy use of its Special Attack Force, better known as the kamikaze. The Allies called these suicide attacks, but they weren’t. However desperate and twisted a tactic - and we’ll get to that in Part II - these were combat deaths, sold to the pilots and the Japanese public as sacrificial offerings.

Sacrifice as a human ideal in Japan came to the fore just over halfway between the time of Christ and the era of the kamikaze. From the 800s to the 1000s, Japanese literature was dominated by nature poetry, intimate diaries, Murasaki Shikibu’s The Tale of Genji and miscellanies like the Pillow Book of Sei Shōnagon - a woman famed for her razor-sharp wit and dripping distaste for Japan’s ‘lower orders.’ (Her list of Unsuitable Things includes ‘snow on the houses of common people.’ Such folk, she thought, were undeserving of moments of fleeting beauty. It is ‘especially regrettable,’ she adds, ‘when the moonlight shines down on it.’)

Sei Shōnagon, as imagined by Kobayashi Kiyochika in 1896

By the early 1200s, a brand-new sort of literature was doing the rounds. It featured, amongst others, a woman named Tomoe Gozen. We meet her in The Tale of the Heike, engaging in some intimate repartee with a man named Uchida, chiding him for his bad manners. So far, so familiar. And yet the exchange takes place not via scented letter or in the moonlit garden of some magnificent aristocratic mansion. They are on a bloodstained battlefield, locked in hand-to-hand combat. And Uchida has Tomoe by the hair:

‘What is wrong with my manners?’ asks Uchida.

Tomoe answered: ‘Does a man good enough to close with a woman draw his dagger as they fight and let her see it? Uchida, you know nothing of the old ways.’

Then she clenched her fist and struck him hard in the elbow of his dagger arm. The blow was so powerful that the dagger fell out of his hand.

‘See . . . ’ she cried, ‘I am from a mountain village in Kiso, acknowledged the best in the land. I am the combat instructor you need!’

And she stretched out her left hand, seized Uchida’s faceplate, and forced his head down on to the pommel of her saddle; then she slipped her hand under the faceplate, drew her own dagger, wrenched the head round and struck it off.

Something was clearly changing in Japan. Before this era, fighting had been left to the unfortunate and often inept conscripts of the Imperial Army. Now, you could make a name for yourself and your family through valiant deeds on horseback or in hand-to-hand combat. Aristocratic Japan, delighting in painting, poetry and fashion, would have regarded ‘martial arts’ as an oxymoron - a nonsensical combining of terms. No longer.

I encountered Tomoe Gozen last week in London, sword in hand (her, not me), while I was force-feeding my children some Japanese culture at the V&A:

This fabulous piece of woodblock art dates back only as far as the early 1800s, but it stands as a record of that earlier, remarkable transition. Whether or not Tomoe Gozen was a real female samurai warrior or a composite character dreamt up for The Tale of the Heike, which recounts a civil war in the 1180s, the samurai and their values began at this point to dominate Japanese life.

We ought not to get too misty-eyed about the long centuries that followed. A samurai was loyal first and foremost to his lord and most were scarcely more tolerant of commoners than aristocrats like Sei Shōnagon. Where Sei would have nature refuse them a blanket of snow for their rooftops, the samurai treated commoners as a source of raw material: rice for their bellies and foot-soldiers for their armies. For a time, the samurai even enjoyed a right known as kiri-sute gomen: should a commoner cause offence, a samurai could cut them down in the street. An enormous amount of innocent blood was spilled, over the years, as rival groups of samurai fought for supremacy.

And yet the samurai came to regard themselves not just as Japan’s security force but as its moral guardians, too. During periods of peace, samurai intellectuals sat down to work out what this ought to look like in practice, heavily influenced as they did so by Buddhism and Neo-Confucianism.

For me, the stand-out value in what came to be called bushidō, the ‘way of the warrior,’ was articulated by Miyamoto Musashi (1584 - 1645). ‘Think lightly of yourself,’ he wrote, ‘and deeply of the world.’

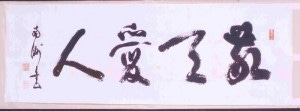

Saigō Takamori, one of Japan’s 19th-century modernisers (and star of The Last Samurai), lived by a similar rule: ‘Revere Heaven, Love Mankind.’

‘Revere Heaven, Love Mankind’ (the Japanese characters are read from right to left).

Unlikely proof of how invested some samurai were in this self-sacrificial ideal came in the 1870s and 1880s. After Saigō and his fellow modernisers put the old Tokugawa shogunate to the sword and got rid of samurai status, a surprising number of ex-samurai converted to Christianity.

Where the shogunate had banned Christianity back in the early 1600s, regarding the worship of an executed criminal as perverse and destructive, ex-samurai of the late 1800s found in it two ideals that they recognised and respected: an ethic of self-sacrifice, embodied in the life and death of Jesus, and profound loyalty to a lord.

One of Japan’s most famous converts, Uchimura Kanzō, went as far as to say that the Apostle Paul had been full to the brim of samurai spirit: independent, money-hating and loyal.

A bronze fumi-e. These were Christian images, often created by apostates, which Japanese who were suspected of retaining their Christian faith were required to step on - thereby repudiating Christianity.

The very notion of bushidō, as we know it now, was the work of a samurai Christian convert named Nitobe Inazō - I wrote about him last week. Other former samurai took their ethic of self-sacrifice and service and ploughed it into medicine, science, politics, education and a range of other professions.

One of the secrets of Japan's rapid modernising success in the late 19th and early 20th centuries was the ability of its new leaders to tap into these old ideals. Japan, they claimed, was in danger. The world was a rough neighbourhood and their country had an enormous amount of catching up to do. Every man, woman and child had to put aside their own personal interests and give everything they had to push their country onwards and upwards.

There was a certain nobility to this ideal, and Japanese Christians were amongst its most fervent supporters. And yet within a few short decades, it had soured - and the results were devastating. We’ll get to that next week.

Samurai on the battlefield would have to remove the noses or heads of their enemies in order to claim their reward. IlluminAsia operates a more humane system: refer friends, help me build the publication and win things in return:

—

Images

Sei Shōnagon: Art Institute of Chicago (fair use).

Tomoe Gozen: Victoria & Albert Museum (fair use).

‘Revere Heaven, Love Mankind’: Samurai Revolution (fair use).

Fumi-e: Bonhams (fair use).

I was recently in Kanazawa and visited a Samurai house. In a room beside the lovely, peaceful garden is a vitrine with swords and other battle paraphernalia. And, this note to the resident samurai, Mr. Nomura Shichirogogo: "We appreciate that you worked so hard to kill one high ranked soldier on the fourth last month at the Yokokitaguchi Battle in Kaganokuni Enumagun. We are happy that you brought us his head." — Dated Oct 9, 1566 (Eiroku Ninth), signed by Yoshikage Asakura (Echizen)

I appreciated the juxtaposition of the serene garden with the casual language acknowledging the beheading.

I look forward to Part 2, Christopher. I'm interested in Japanese history, and this parallelism between the concept of Christian sacrifice and the way of the Samurai makes for a great read. Thank you!