It’s one of the most famous questions in the history of comedy, raised in The Life of Brian (1979) at a meeting of the People’s Front of Judea: ‘What have the Romans ever done for us?’ A little shy and hesitant at first, members of the group begin to speak up. The aqueduct? Sanitation? Education...?

What if you asked the Romans what Asia had ever done for them? Pliny the Elder (23 – 79 CE) would gladly have put a figure on it for you: 50 million sesterces’ worth of trade every year, he once claimed.

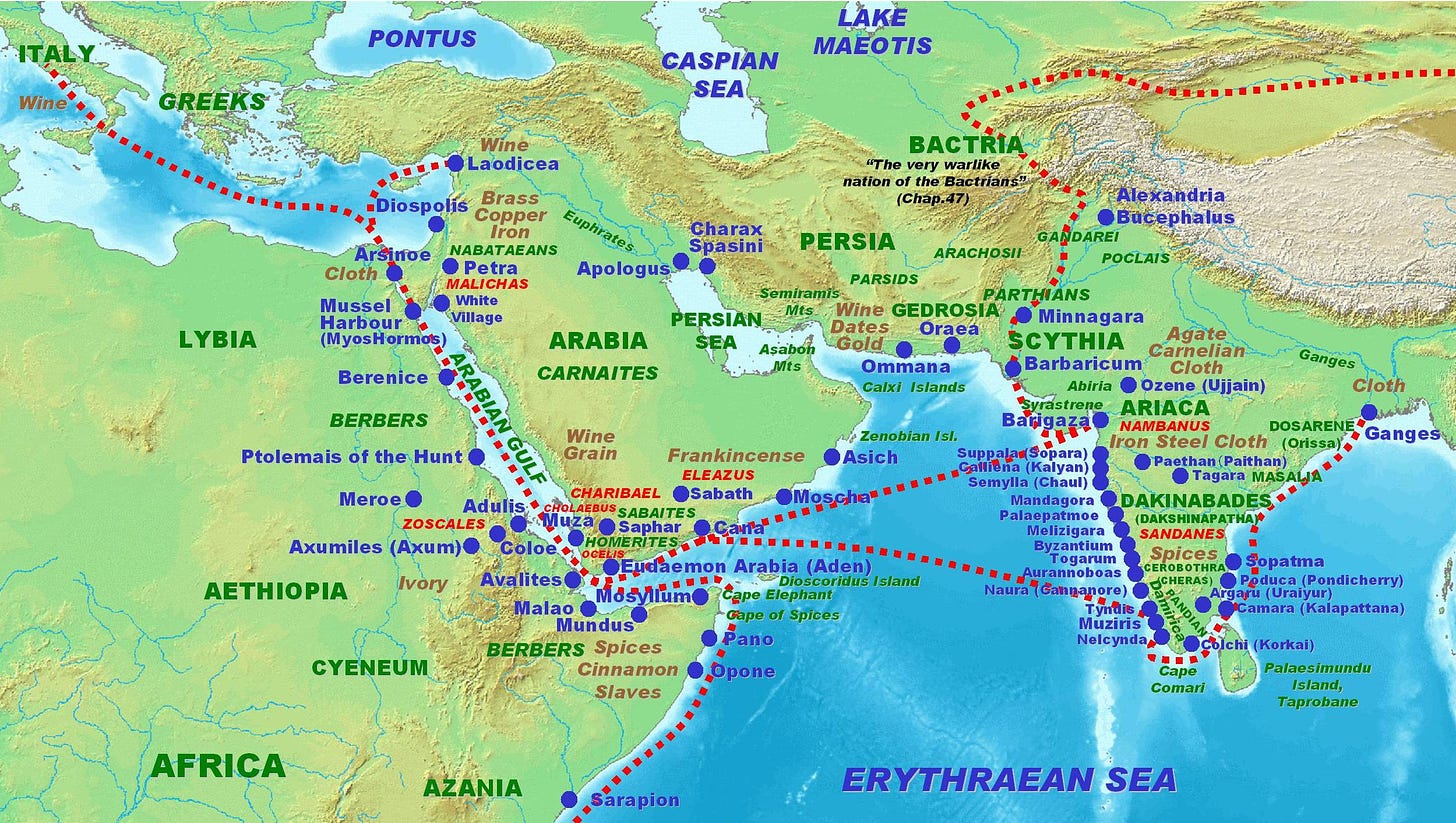

Sadly, from Pliny’s point of view, that was the figure for money leaving the Roman Empire and heading to India. Merchants had begun travelling to the subcontinent in large numbers a few decades before, during the reign of Emperor Augustus (27 BCE – 14 CE). Some went over land, others travelled on ocean-going ships departing from Red Sea ports.

Armed with companies of archers - protection against pirates - along with new-found knowledge of the seasonal monsoon winds, they set sail for a handful of ports on India’s western coast. Everything from Spanish olive oil and terracotta jars to slaves and mercenaries was carried aboard, to be exchanged for Indian perfumes, precious woods and copious quantities of pepper.

Indo-Roman trade in the first century CE

Pliny did not approve of Romans’ love of pepper. Not could he abide his countrymen’s penchant for diaphanous silk - so thin, he claimed, that it gave the wearer ‘the appearance of near-nakedness’. Fortunately, India had become, by Pliny’s time, a source not just of corrupting luxuries but of moral exemplars too. Cicero (106 – 43 BCE) was one of the first Roman writers to praise the endurance of Indian religious ascetics and to suggest that the Indian practice of sati – a widow’s self-immolation on her husband’s funeral pyre – represented the kind of determined wifely devotion to which Roman women ought to aspire.

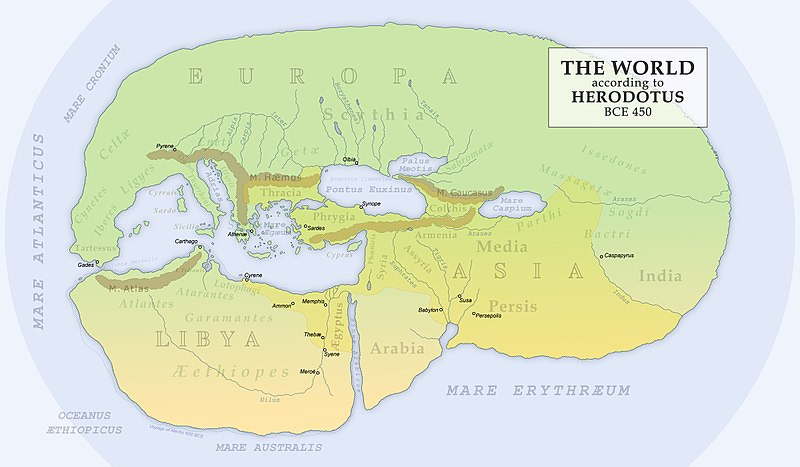

Alongside luxuries and lessons in moral conduct ran a third strand within Western interest in Asia: stories. These went all the way back to the time of the Greek historian Herodotus (484 – 425 BCE). Many in his era imagined the earth to be a cylinder, with a collection of continents on the top, bounded by a perpetually circulating ‘River Oceanus.’ India, Herodotus believed, was the furthest east that you could go. Beyond that one would find only desert and finally the eternal river.

Herodotus had heard, largely from Persian informants, that this ‘India’ was home to ants that burrowed deep into the earth and brought gold dust to the surface when they returned. A sensationally strange range of semi-human creatures, too, called India home. They included one-legged people whose single foot was big enough to serve them as a sunshade at noon.

As the years passed, more was added to this mental menagerie, from dog-headed men and human beings missing various key bits of anatomy – amongst them the ‘nose-less ones’ – to the fearsome ‘martichora’, or ‘manticore’. This was a lion-like beast with a human face and three rows of teeth in each jaw. Its scorpion tail was said to fire foot-long stingers at anyone foolish enough to come too close.

Above: a ‘sciapod’: just one of India’s notable inhabitants.

Below: the legendary martichora.

Where did all this come from? It was a mixture, for the most part, of religious myth and rumour. Stories and images of Indian gods and goddesses made their way from Indian informants via Persian middlemen to Greek ears, becoming twisted and confused along the way.

In Herodotus’ day, after all, few Westerners had actually travelled to India. Even when they did so, most famously in the entourage of Alexander the Great during his invasion of north-west India in the mid-320s BCE, old fantasies died hard. A good story was worth a great deal – not least to writers seeking to build a following back home, amongst people who had been raised on epic Greek drama.

Best of all was when a wild tale turned out to be true. Ancient sceptics regarded as hilariously gullible anyone who believed that there existed in India animals capable of uprooting trees and smashing down city walls. And yet Alexander arrived in India to find some of his enemies careering around atop these big grey monsters – elephants, to you and me.

An imagined scene from Alexander the Great’s campaign in India. War elephants can be seen in the top-right corner

It was in India that Alexander’s great journey eastward came to an end. Some say that the armies arrayed against him – including war-elephants – were simply too strong. Others claim that his men had had enough: they had arrived in India expecting to find a smallish country and the fabled River Oceanus beyond – you could see that great river, it was claimed, from atop the Hindu Kush mountain range. Instead, India seemed to go on forever. It was time to turn back and head home.

Alexander never made it home, dying along the way. But his successor in the region, Seleucus I Nikator, sent an ambassador named Megasthenes to the court of one of India’s great rulers: Chandragupta (350 BCE – 295 BCE). The result was an account of India, known as Indica (c. 300 BCE), which combined brand-new and relatively accurate information about India – politics, social arrangements, flora and fauna – with what would become a major theme in Western interest in Asia: hubris.

For Megasthenes, the story of India was one of a rather backward land of nomads - who ate animal flesh uncooked, with a side-serving of tree-bark - who had received two civilising visits in the distant past. The first was from the Greek god Dionysus, a son of Zeus. He was said to have brought settled agriculture to India, alongside architecture, law, wine and much else besides. Heracles, another son of Zeus, followed later, and amongst his gifts was a daughter called Pandaea, who went on to become an Indian queen.

Megasthenes found evidence of a kind for these claims in the similarity of Indian religious rituals – cymbals, drums, music – to their Greek counterparts. At a deeper level, it seemed natural to him that all peoples of the Earth would be subject to the same gods. Asia’s contributions to life in the ancient western world did not extend to challenging people’s sense of ultimate Reality.

Then again, though we have little evidence of western conversions to Asian philosophies in this era - bar some tantalising evidence of Roman traders becoming Buddhists while in India - that did not mean that contact with Asia failed to extend westerners’ sense of Reality’s range.

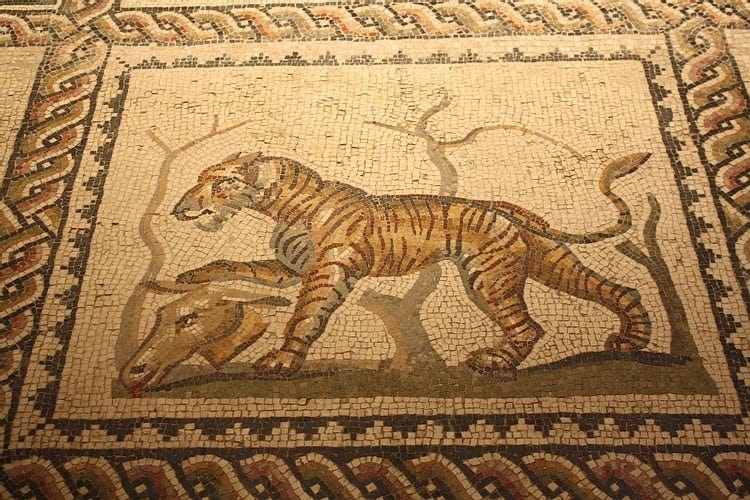

Emperor Augustus was gratified to receive embassies from south Indian kings, since not even Alexander the Great - a legend in Augustus’ time - could have claimed that kind of geopolitical pull. But perhaps there were moments when Augustus put politics aside and simply marvelled at having a tiger in his midst, shipped from India as part of one of the embassies and now prowling with power and menace around its cage. The world, Augustus might have reflected, was a good deal larger and stranger than he had previously imagined.

A floor mosaic of a tiger, from southern Italy c. early third century CE.

Part II - The Medieval World - is HERE.

Suggested Reading:

Daniela Dueck, Geography in Classical Antiquity (Cambridge University Press, 2012)

Richard Stoneman, The Greek Experience of India: From Alexander to the Indo-Greeks (Princeton University Press, 2019)

Tom Holland, Herodotus: The Histories (Penguin, 2014)

Image credits:

Indo-Roman trade in the first century CE: Creative Commons

Herodotus’ map of the world: Creative Commons

Sciapod: Theoi.com (fair use)

Martichora: Creative Commons

Imagined scene from Alexander the Great’s campaign: WarfareHistoryNetwork.com (fair use)

Tiger mosaic: WorldHistory.org (fair use)