Part I - the Ancient World - is HERE.

Ancient Roman writers like Pliny the Elder (23 – 79 CE) were famous for criticising their countrymen’s indulgence in Asian luxuries. They would no doubt have found it bitterly fitting, then, that in 410 a once-mighty Rome was reduced to begging a barbarian army to leave its people in peace - offering gifts of Asian silk and pepper if only king Alaric and his Goths would go away.

The gambit failed and Rome was sacked, but Europeans’ taste for spice lived on. Across the centuries that followed the collapse of the western Roman Empire, cinnamon, saffron, cloves, nutmeg and pepper could be found jazzing up the taste and look of savoury dishes served up at grand banquets across the continent. They were used in medicine - as a constipation cure and as medieval Viagra - and also in Christian religious rituals, as they moved from the homes of the faithful into new, purpose-built churches.

Scene from a medieval ‘Book of Hours’, showing a potentially spicy feast

Quite where these spices came from, most Europeans would not have been able to tell you. People’s sense of global geography was frustrated by the rise of Islam from the 600s onwards - which cut Europeans off from most of Asia for a while - and a sometimes awkward blend of ancient Greek cartography with claims about the Earth found in the Bible.

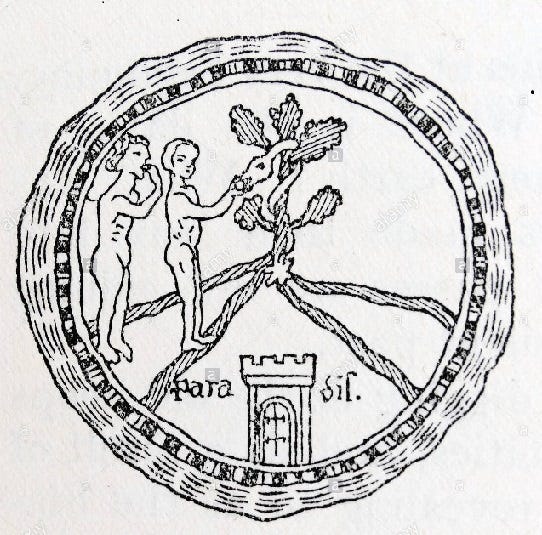

Major Christian thinkers like Augustine of Hippo interpreted literally the claim in the book of Genesis that the Garden of Eden was located somewhere to the east of Asia. It was said to be watered by a great river, which split into four ‘rivers of paradise’ at the point where it entered the ordinary mortal realm.

One of those rivers was the Tigris, another was the Euphrates. A third was ‘Pishon’, associated with a waterway somewhere in India: sometimes the Ganges, sometimes the Indus. Last but not least was ‘Gihon’, usually identified with the Nile. Some in medieval Christendom believed that spices grew on trees in the Garden of Eden. Blown by breezes into Eden’s river, they made their way from there into Asia.

Above: a simplified (French) version of a ‘Mappa Mundi’ held in Hereford Cathedral. The map is oriented to show Paradise at the top, located to the far east of the world. Jerusalem is at the centre.

Below: one of many pieces of Christian symbolism showing Adam, Eve and the four rivers of paradise.

Spices were regarded as all the more sacred for their closeness to Paradise. Pious and entrepreneurial Europeans alike thus found it rather galling that the geopolitics of the day allowed Arab Muslim traders to make a tidy profit as spice-dealing middlemen: fortuitously located between the sources of spice in Asia and a heavily-addicted European clientele.

In the latter half of the 1100s, a hopeful - even desperate - rumour began to do the rounds in Europe, fuelled by a letter said to have been written by a powerful and fabulously wealthy Christian king living in India. The vast and fertile lands of ‘Prester John’ apparently boasted emeralds and sapphires, a spring whose waters would fix your age forever at 32 if you drank from them, and a great mirror in which the king could see all that went on in his kingdom.

Europeans waited in vain for Prester John to arrive with his fabled armies and help them bring the Crusades to an end. It fell instead to Genghis Khan (1162 - 1227) to open up Asia for Europe once again. His conquests across vast swathes of central Asia made it possible for Europeans to travel overland, and in relative security, all the way to China.

Amongst those who claimed to have done just that in the second half of the 1200s was a Venetian merchant’s son by the name of Marco Polo. Captured in a sea battle in 1298, fought between two great maritime republics - Venice and Genoa - Polo shared a prison cell for a time with a romance writer named Rustichello. Out of their incarceration came The Travels of Marco Polo: an account of eastern explorations so far-fetched that Polo’s friends urged him on his deathbed to recant his lies for the sake of his soul.

Above: a map of what Marco Polo claimed were his travels

Below: An illustration from one of the many editions of Marco Polo’s book

In fact, much of what Polo claimed seems actually to have happened. He travelled with his father Niccolò and uncle Maffeo to the court of Kublai Khan in China, in 1273 or 1274. Whether Polo served Kublai Khan as an administrator and emissary, as he claimed, is hard to say with certainty. Chinese records make no mention of anyone by that name. But Polo’s descriptions of China have been shown to be strikingly accurate.

This, in fact, was part of the problem for Polo’s contemporaries. Few Europeans having travelled to China up until this point, the country was something of a blank canvas. Onto it, Polo’s audience hoped that he would paint unicorns, other strange and wonderful beasts - and perhaps even Prester John.

Polo broke their hearts. He claimed to have seen these ‘unicorns’ on his travels, but insisted that they were ‘very ugly’, with a penchant for wallowing in mud - Polo seems to have been describing a rhinoceros. The legend of Prester John meanwhile had its origins, claimed Polo, with a rebellious Mongolian warlord. That warlord was now dead, having been put to the sword by the Great Khan.

The real China, in Polo’s telling, was a highly-civilised place. It had paper money and postal services. It had well-populated cities served by networks of canals. And it had well-respected rulers, who lived in gorgeous lakeside homes and enjoyed pleasure-cruises on large and luxurious boats.

That a far-off, non-Christian land could be flourishing to this extent was not generally regarded as welcome news in Europe. More palatable by far was Polo’s mention of an entirely undiscovered country: ‘Cipangu’, later known as Japan:

Cipangu is an island that lies out to the east [of China] in the open sea, 1,500 miles from the mainland. It is an exceptionally large island. The people are white, good-looking and courteous. They are idolaters and are completely independent, having no rulers from any race but their own. Moreover, I can tell you that they are exceedingly rich in gold, because it is found here in inestimable quantities.

The only downside for potential visitors to Cipangu, reported Polo, was the risk of being taken prisoner and then ransomed. If your nearest and dearest failed to pay up, you would be killed, cooked and served for dinner – perhaps with a seasoning of black and white pepper, in which Cipangu was said to abound.

The opulent but deadly island of Cipangu, as imagined by an illustrator of Marco Polo’s book

Marco Polo heard good things about the Buddha on his travels, and he met some of India’s holy men during a long and circuitous journey home to Italy. But what seems to have stuck in the minds of budding European adventurers was all that talk of gold. Alongside the prospect of easy access to spices it proved enough to persuade the Genoese navigator Christopher Columbus to try, two centuries after Polo’s return from China, to reach Asia by travelling westwards over water.

There were still those, in this era, who believed the Earth to be a flat disc. For them, sailing west in hopes of ending up in the far east was both stupid and dangerous. But thanks to the efforts of Islamic scholars, who had for centuries been making ancient Greek texts available to medieval Europe, Columbus possessed Ptolemy’s second-century Geography, with its detailed mapping of a spherical Earth.

The Geography proved not to be an entirely infallible guide: Ptolemy had known nothing of what came to be called the ‘New World’. For his part, Christopher Columbus preferred to deny its existence, despite having actually been there. Instead he continued to insist, right up to his death, that he had made it to Asia.

No matter: Columbus’s Spanish backers were quite content with all the precious metals to which the New World turned out to be home. A rival navigator by the name of Vasco da Gama meanwhile found a way around the continent of Africa and out into the Indian Ocean, during a voyage made in 1497-8. Asia, and those precious spices, seemed at last to be within reach.

Part III - The Early Modern World - is HERE.

Suggested Reading

Paul Freedman, Out of the East: Spices and the Medieval Imagination (Yale University Press, 2009)

Marco Polo, The Travels, with an Introduction and Notes by Nigel Cliff (Penguin reprint, 2015)

Valerie Flint, The Imaginative Landscape of Christopher Columbus (Princeton University Press, 1992)

—

Images

Book of Hours: Archive.org

Hereford Mappa Mundi: Pinterest (fair use)

Adam, Eve and the rivers of paradise: Longsworde (fair use)

Map of Marco Polo’s travels: Creative Commons (public domain)

Illustration from Il Milione: Creative Commons (public domain)

Cipangu: AKG Images (fair use)