Part IV - Towards the Modern World - is HERE.

‘My dear Mrs Besant, if you would only come among us!’

This moment became a tipping point for Annie Besant: atheist, socialist and a passionate advocate for women and the poor in Britain. She had gone over to the home of Helena Petrovna Blavatsky in London’s Holland Park, to interview her about her recent book. The Secret Doctrine (1888) conjured a grand vision of the cosmos, drawing on Egyptian and Graeco-Roman religion, magic, Jesus Christ, Jewish Kabbalah, astrology and alchemy, modern science, Hinduism and Buddhism.

Each person’s role in this cosmic drama, thought ‘Madame Blavatsky’, as she was known, was to undertake a spiritual odyssey spanning many lifetimes. The journey began with a soul’s emergence from the Absolute, or ultimate Reality, and ended with its final return.

The Secret Doctrine was an extraordinary – and extraordinarily influential – piece of work, a milestone in the West’s encounter with Asian wisdom. A great many people in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries credited Theosophy with helping to awake in them an interest in Buddhism or Hinduism - including a young lawyer named M.K. Gandhi, who met Blavatsky and Besant while studying in London.

And yet for Besant, more impressive than Blavatsky’s book was the experience of encountering her in person. Blavatsky sat there rolling cigarettes and recounting her travels to far-off places, steering clear of all talk of the occult until the very last moment, when she invited Besant to become a part of the ‘Theosophical’ (divine wisdom) movement that she was building.

Besant recalled it as an experience of being known, and chosen. ‘I felt a well-nigh uncontrollable desire,’ she recalled, ‘to bend down and kiss her, under the compulsion of that yearning voice, those compelling eyes.’

Above: ‘Madame’ Helena Petrovna Blavatsky

Below: Annie Besant

Besant’s conversion to Theosophy - she went on to become one of the movement’s most influential writers and speakers - was an early sign of something new happening in the West’s relationship with Asia.

The old threads were still there: a hunger for exotic goods and stories, a desire for wealth and power – this was, after all, the high noon of the British empire – and a tendency to compare Asian societies and cultures unfavourably with western life.

And yet in amongst all this was a growing sense of need amongst westerners, for philosophical and spiritual renewal. The old certainties no longer spoke to them, or commanded their attention and affection. Asian poetry, myths, rituals and beliefs went from being merely interesting or picturesque to possessed, at least potentially, of a superior genius and power.

Much of this new promise was mediated through the writings of great popularisers of Asian thought. But these were intimate, subtle matters, so personalities and personal encounters came to count for a great deal, too.

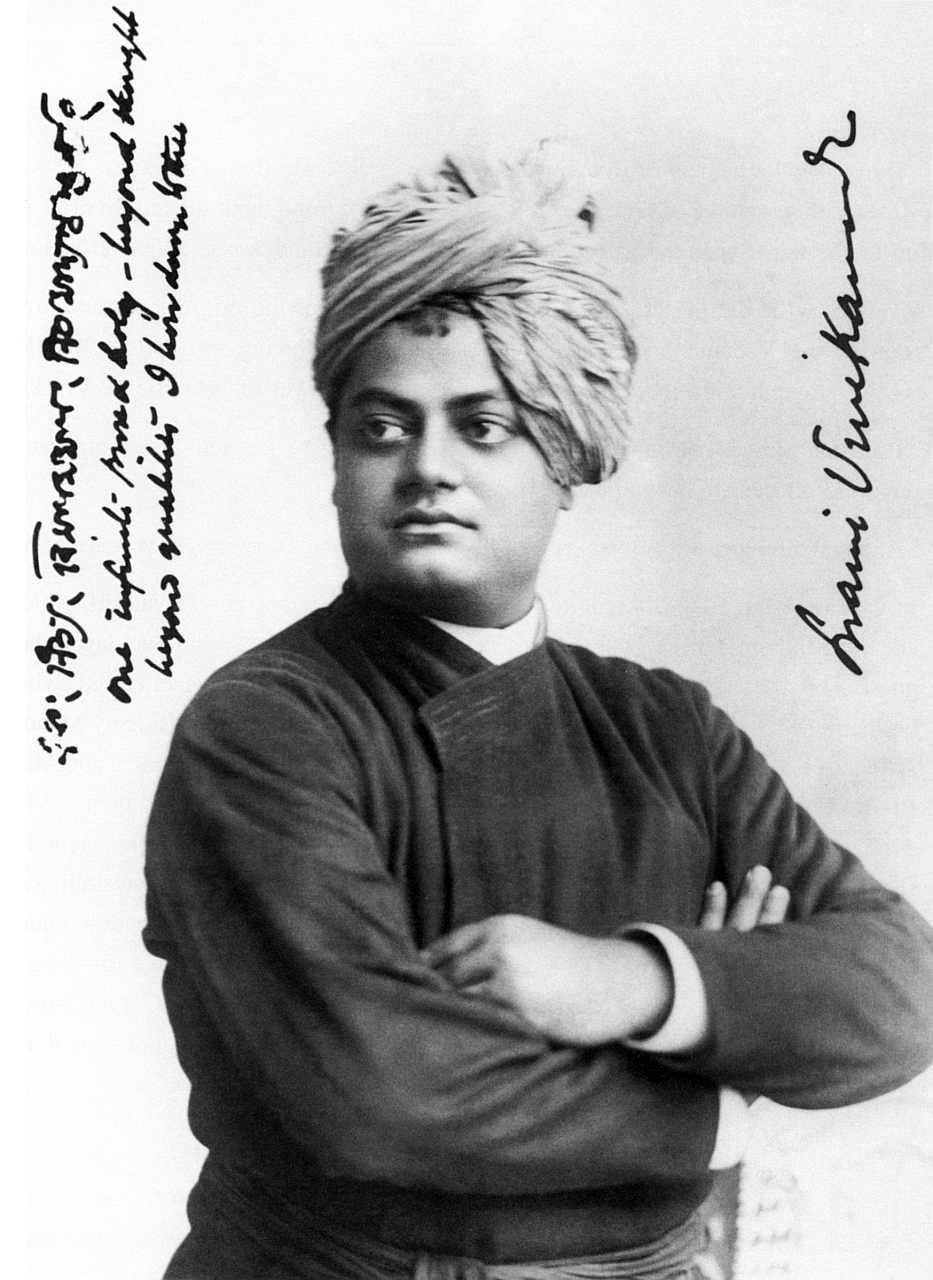

One of the great pioneers of this new era was the Indian religious teacher Swami Vivekānanda. He became the star of the ‘World’s Parliament of Religions’ (WPR), convened in Chicago in 1893. Speakers on Asian traditions and the occult, including Annie Besant, addressed packed-out rooms while Christian speakers had to grit their teeth as the opening lines of their speeches were drowned out by the sound of people making for the door. There it was: hunger for something fresh and compelling.

Pitching his own particular brand of Hinduism, known as Advaita Vedānta, Swami Vivekānanda helped set the tone for western religious and spiritual searching in the twentieth century. His first big theme was universalism. Hindus, he declared, acknowledged that all religions possess deep truth, and can serve as paths towards the same destination – God, or the Absolute.

Second, Vivekānanda insisted that Hinduism was entirely compatible with modern science. This was a point on which many Christians were struggling, as new discoveries in physics and biology made it more difficult to see how humanity and the world at large could be the meaningful, purposeful creation of a loving God. The cosmos seemed characterised instead by stuff, chance and vast empty spaces.

Third, Vivekānanda showed sympathy for westerners who felt that their societies’ enormous recent strides in technology, industry and the projection of power around the globe had come at the cost of their souls. Materially prosperous, they were spiritually impoverished: mired in a crisis of meaning that their religions and philosophies appeared powerless to address.

Above: view across the ‘White City’: a constellation of temporary structures built near Chicago to house the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition, celebrating - a year late - the quadricentennial of Christopher Columbus’ famous voyage westward.

Below: The World’s Parliament of Religions was part of this Exposition, and Swami Vivekānanda was its break-out star.

Inspired by teachers like Vivekānanda, growing numbers of westerners turned to Asian traditions in their search for meaning. Zen Buddhism took off in the years after the First World War, promising an immediate, down-to-earth and doctrine-light approach to the religious life.

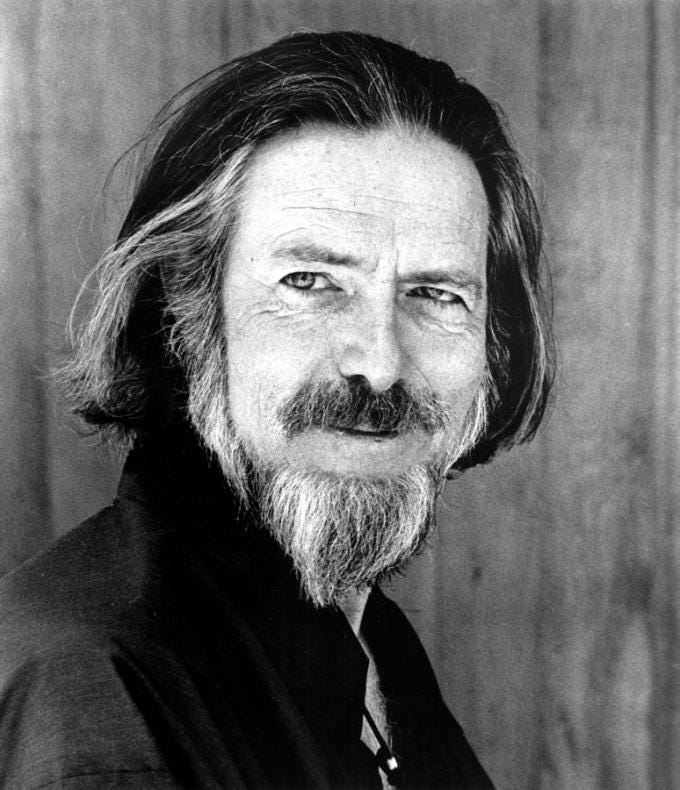

Thanks to gifted popularisers like the English philosopher Alan Watts, various strands of Asian thought including Zen, Taoism and Vedanta were offered as an antidote to western materialism and spiritual decay. The psychology of Carl Jung became influential in making the case, especially Modern Man in Search of a Soul (1933) with its critique of unhealthy individualism, loneliness and an over-reliance on reason in understanding and living in the world.

For Watts, liberation from anxiety was ultimately a matter of feeling - immediately and profoundly - one’s connectedness with the world around. Indian, Japanese and Chinese religious traditions, he thought, were better equipped than western Christianity to help people towards this experience.

Watts moved to San Francisco in the early 1950s, just in time to see spiritual concerns like these turn thoroughly political. Desperate to avoid their parents’ prosperous but apparently purposeless lives, young Americans threw in their lot with the Beat and hippie generations. ‘Eastern’ mysticism, LSD, anti-war protest and the sound of the sitar all came together, helped along by pop culture of all kinds, including the Beatles’ brief flirtation with transcendental meditation.

Above: Alan Watts, pictured in the 1960s in trademark goatee and kimono.

Below: an excerpt from one of Watts’ talks, animated by the creators of South Park.

Above: The Beatles’ Norwegian Wood (1965) has a good claim to be the first western pop song to include a sitar.

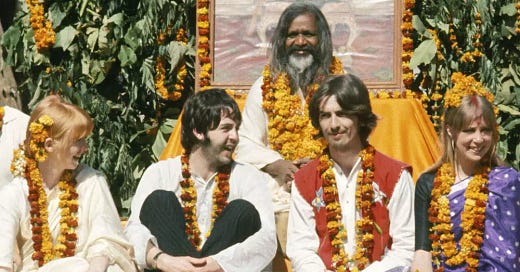

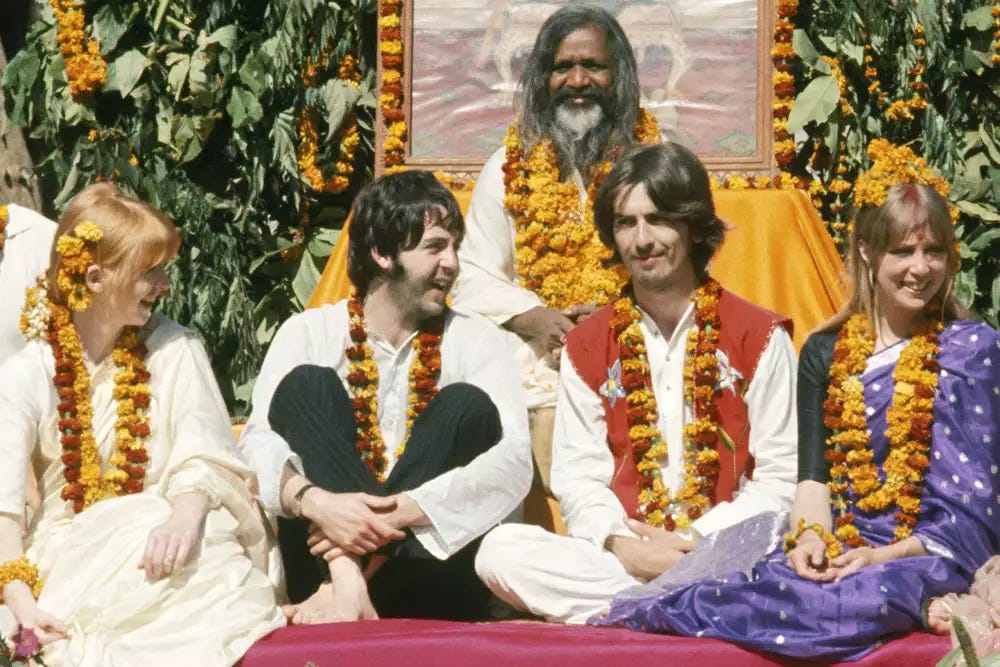

Below: the Beatles in Rishikesh, India, in 1968, studying with Maharishi Mahesh Yogi.

Boom was, almost inevitably, followed by bust. After reaching a peak of sorts in the era of the Beatles and then Star Wars - ‘the Force’ owed much to George Lucas’ reading about Hinduism - a sense of cliché and cultural caution began to set in, around the western search for meaning in Asia.

The popularity of yoga and meditation has fluctuated in the years since, always having to contend with pop culture stereotypes - the Karate Kid franchise; Indiana Jones battling dusky, Brahmin-like bad guys - alongside awkwardness and sometimes outright condemnation at the sight of westerners taking up Asian practices and ideas.

‘Luminous beings are we, not this crude matter.’ Yoda serves as guru to Luke Skywalker in The Empire Strikes Back (1980)

Much of this is still with us: a meaning crisis, a vexed relationship between science and religion, the sense that there is much to learn from Asian traditions like Buddhism combined with feelings of disquiet about crossing cultural boundaries. IlluminAsia will have much to say about it all, in the coming months.

For now, just three points by way of conclusion to this short series on ‘What has Asia ever done for us?’ - all of them courtesy of the one Beatle who remained serious about meditation: George Harrison, who famously leant his support to the Hare Krishna movement, even helping them to get onto Top of the Pops.

Harrison read the Bhagavad Gita to his mother on her deathbed. He was, in other words, serious about his new-found commitment. And yet, as his girlfriend Pattie Boyd and others could attest, that hardly made him perfect. He could be arrogant, cold and unfaithful. He had days when he felt so low that he flew a skull-and-crossbones flag from his home. None of this amounted to failure: it was a sign of real engagement with Asian thought, which took time to work out and could be messy and unpredictable.

Second, having encountered Indian thought thanks to Ravi Shankar, who taught him to play the sitar and introduced him to the writings of Swami Vivekānanda, Harrison allowed it to become intimate and personal to him - much as Besant had done with Theosophy, thanks to Madame Blavatsky. Vivekānanda would no doubt have approved: the universalism that he taught, beyond ‘East’ and ‘West’, could only ever become a reality within a given person’s life. Otherwise it remained a matter of mere rhetoric, show, or shifting fashion.

Lastly, Harrison understood that when it comes to life’s big questions people rarely find inspiration in only one place. Books, meditation and rituals are all very well. But music, as he knew better than most, has its own way of reaching people.

George Harrison’s My Sweet Lord (1970)

Since Harrison’s death in 2001, western interest in Asia has continued to grow far beyond the high philosophy and spirituality with which it was associated for so much of the twentieth century.

We’ll be exploring much of this in IlluminAsia: travel, novels, children’s animations, action and horror films, food, dance, history, art and theatre. Some of it is bound up, still, with people’s search for meaning beyond the culture into which they were born. All of it is connected with what western interest in Asia has, at its best, always been about: the thrill of discovery, and an openness to reimagining the world - all the way down.

—

Suggested Reading:

Annie Besant: An Autobiography (1893)

Ruth Harris, Guru to the World: the Life and Legacy of Vivekananda (Harvard University Press, 2022)

Monica Furlong, Zen Effects: the Life of Alan Watts (2001)

Joshua M. Greene, Here Comes the Sun: the Spiritual and Musical Journey of George Harrison (2006)

—

Images

‘Madame’ Helena Petrovna Blavatsky: Creative Commons (public domain).

Annie Besant: Creative Commons (public domain).

View across the White City: Creative Commons (public domain).

Swami Vivekānanda: Creative Commons (public domain).

Alan Watts: The Marginalian, courtesy of the Everett Collection (fair use).

The Beatles in India: Times India (fair use).