Part III - The Early Modern World - is HERE.

In 1589, the Elizabethan collector and publisher of travel accounts Richard Hakluyt made a very bold claim. The English, he wrote, are ‘men full of activity, stirrers abroad, and searchers of the remote parts of the world’.

It was a bold claim because there was precious little evidence for it. Travel literature in English, as Hakluyt knew only too well, consisted overwhelmingly of translations from Italian, Portuguese and Spanish – parts of Europe that really were responsible for stirring things up abroad, for better and for worse.

Across the 1500s and 1600s, most Englishmen saw better prospects to their west – in North America – than they did to the east, in Asia. A handful of Englishmen journeyed to Mughal India in the late 1500s and early 1600s, to see whether they might chip away at Portuguese influence there and in the process top up their coffers or enhance their reputation back home. But it wasn’t until the eighteenth century that the East India Company (EIC) began to engage in the sort of activity that would have made Richard Hakluyt proud.

Above: the Mughal Empire at its zenith. Portuguese territory in India only ever amounted to small enclaves such as Goa on the south-west coast.

Below: a collection of letters written by the English traveller Thomas Coryate, who spent time at the Mughal court in the early 1600s during the reign of Emperor Jahangir

The East India Company (EIC) was founded in 1600, as a means for Englishmen to muscle-in on the Asian trade. Its first century of life was relatively unremarkable. Representatives sent to the court of the Mughal emperors were humoured more than they were respected, and most returned to England having fallen far short of the sort of trade deals craved by their bosses in London.

It was only when the Mughal empire began to fall apart, in the early 1700s, that the EIC got the chance to expand its influence. Fortified trading stations had already been established, at Madras (in 1639), Bombay (1668) and Calcutta (1690). But now a combination of deal-making and war-making began to bring ever larger parts of the subcontinent under East India Company control.

Most valuable of all was the territory of Bengal, in eastern India. The EIC won control of it at the Battle of Plassey in 1757, and senior Company men like Robert Clive set about extracting land revenue and other forms of wealth besides - sending boats laden with looted treasure bobbing down the Hughli River.

Above: Robert Clive, who led EIC forces at Plassey in 1757, meets Mir Jafar, the general whose defection to the EIC side helped to win the day.

Below: map of India in 1765, showing newly-won British possessions in the east.

Such were the sums of money soon being made by the likes of Clive, and the corrupt means of doing so – which contributed to famine in Bengal in 1770 - that Parliament was forced to change the terms of the EIC presence in India. A post of Governor-General was created in 1773, and a Supreme Court followed soon afterwards.

Aspiring, now, not just to trade or collect taxes in India but actually to rule, the English began to explore Indian justice for the first time. In doing so, they encountered some of the country’s sacred texts. Prime amongst these were four ‘Vedas’ (‘knowledge’ in Sanskrit), the earliest of which dated back to around 1500 BCE.

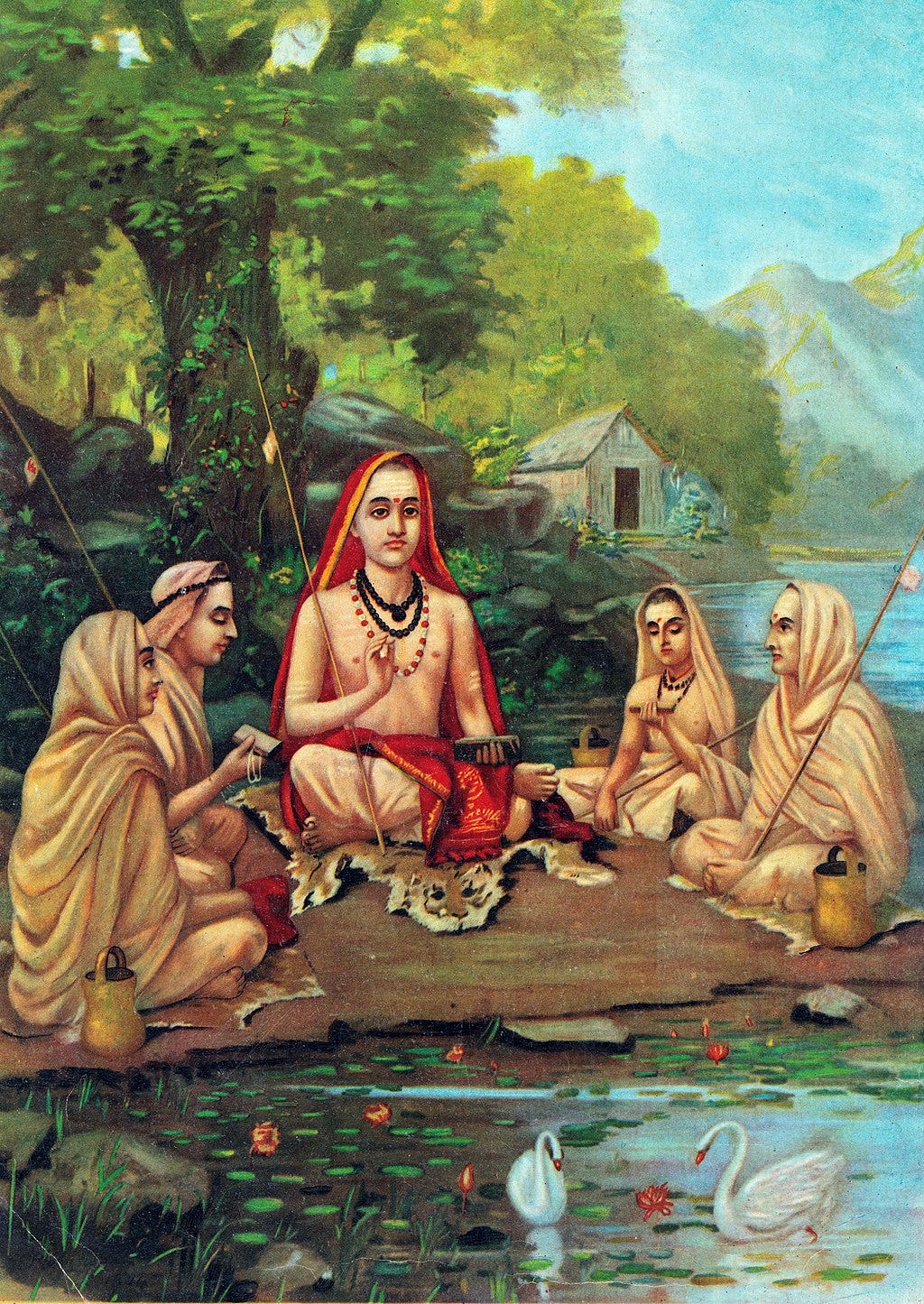

Spiritual commentaries appearing at the end of these Vedas were called ‘Upanishads’. This was a Sanskrit word comprising upa (near), ni (down) and shad (sit), giving the sense of sitting down near a spiritual teacher to receive wisdom. Some of these Upanishads were perhaps being composed when Alexander the Great’s armies stormed into India, back in the 320s BCE.

Various schools of philosophy were discovered, too, alongside epic stories of gods and men. Two of the greatest had been put together between 300 BCE and 300 CE. The Rāmāyana (‘Rama’s Journey’) told the story of the deity Rama, including the kidnapping and rescue of his wife Sita. The Mahābhārata (‘Great Epic of the Bhārata Dynasty’) centred around five brothers, the Pandavas, waging war against other members of their extended family.

The best-known section of the Mahābhārata was the Bhagavad Gita, the ‘Song of the Lord’. One of the Pandava brothers, Arjuna, converses with his charioteer, who turns out to be the deity Krishna. It begins with Arjuna’s anxieties about the battles and bloodshed to come, and turns into a philosophical discourse on how to live.

Scene from the Bhagavad Gita, showing Arjuna and Krishna in conversation

English interest in India’s religious literature began with the desire to rule the country more effectively. In his prefatory letter to the first English translation of the Bhagavad Gita, Governor-General Warren Hastings praised its content - comparing it with the Iliad - while noting that ‘every accumulation of knowledge is useful to the state’.

For some, however, including the poet and lawyer William Jones, pragmatism turned to affection and respect. While serving as a judge on Calcutta’s Supreme Court, Jones studied Sanskrit, translated religious texts and wrote hymns to Indian deities as a way of sharing Indian wisdom with audiences back home:

Delusive Pictures! unsubstantial shows! My soul absorb’d One only Being knows, Of all perceptions One abundant source, Whence ev’ry object ev’ry moment flows: Suns hence derive their force, Hence planets learn their course; But suns and fading worlds I view no more: God only I perceive; God only I adore.

— From William Jones’ Hymn to Narayena (1785)

The influence of Indian literature in Europe was profound, especially when communicated by people with Jones’ talent for presentation. For much of the eighteenth century, Chinese arts and fabrics had been in great demand. Thinkers like Voltaire had found in China’s political system much to admire: it was controlled, day to day, by educated, secular men – people much like himself, in fact. But as China’s star waned in the late 1700s, Europeans increasingly turned to what they regarded as the purity and contemplative depth of Indian wisdom.

Goethe was a fan, and so, too, Samuel Taylor Coleridge. Both men were drawn in particular to the Advaita Vedānta philosophy of Śankara (eighth century), which spoke of the everyday world as maya – illusion – veiling a glorious Reality beyond.

Above: François Boucher’s ‘The Chinese Garden’ (1742)

Below: Raja Ravi Varma’s portrait of Śankara (1904)

Later in the nineteenth century, parts of the West passed through a Buddhism boom, inspired in no small part by another poet: Edwin Arnold, whose account in verse of the Buddha’s life – The Light of Asia – was drafted on restaurant menus, shirt cuffs and anything else that came to hand. When finally published as an actual book, in 1879, it proved popular enough to persuade worried Christians to pen book-length rebuttals.

As with Jones and Indian philosophy (or ‘Hindu’ philosophy – the word was a colonial creation), Arnold was drawn to what he regarded as the purity, psychological good sense and idealism of the Buddha’s teachings. Where western critics of Buddhism regarded it as nihilistic, seeking not the salvation but the extinction of the self, Arnold depicted the moment of the Buddha’s enlightenment as one of blessed relief:

Never shall yearnings torture him, nor sins

Stain him, nor ache of earthly joys and woes

Invade his safe eternal peace; nor deaths

And lives recur. He goes

Unto NIRVANA. He is one with Life,

Yet lives not. He is blest, ceasing to be.

OM, MANI PADME, OM! the dewdrop slips

Into the shining sea! Arnold remained a Christian all his life, and Samuel Taylor Coleridge eventually chose Christianity over Indian idealism – regarding the latter, with bitter disappointment, as a ‘painted Atheism’. But Asian religion and philosophy were increasingly recognised across much of the West as sophisticated, plausible and even - to some - compelling.

As more and more Westerners began to question Christianity, thanks in part to new scientific and archaeological discoveries which threatened to undermine key tenets of the faith, the attractions grew of Buddhism in particular.

From the late nineteenth century onwards, advocates for Vedānta and Buddhism - Asian and western alike - presented them as ideal answers to tired, disenchanted modern minds: relatively light on complex historical or cosmic claims, and focused instead on helping people to flourish in the world - ethically, psychologically, spiritually. The stage was set for some of the great spiritual odysseys of the twentieth century.

Part V - The Twentieth Century and Beyond - is HERE.

Suggested Reading:

William Dalrymple, The Anarchy: The Relentless Rise of the East India Company (Bloomsbury, 2019)

Nandini Das, Courting India: England, Mughal India and the Origins of Empire (Bloomsbury, 2023)

Michael J. Franklin, Orientalist Jones (2011)

Images:

The Mughal Empire: MEMOs (fair use)

Thomas Coryate: MEMOs (fair use)

Aftermath of the Battle of Plassey: Creative Commons (public domain)

Map of India in 1765: Creative Commons (public domain)

Scene from the Bhagavad Gita: Sivananda Yoga Vedanta Center (fair use)

François Boucher’s ‘The Chinese Garden’’: Creative Commons (public domain)

Raja Ravi Varma’s portrait of Śankara: Creative Commons (public domain)