The first rule of Substack is You Do Not Talk About Substack.

Not really. The first rule of Substack is that you should post regularly. I’ve been away for the summer, so haven’t quite managed that. But here we are, back in the saddle, with a series of essays on IlluminAsia exploring a single question: What Makes a ‘True Story’?

If it’s taboo on Substack to post irregularly, it’s surely taboo, too – anywhere – to start banging on about Christmas in early October. Rest assured: that isn’t what I have planned.

I do want to explore, in the final essay of the series, the Christian nativity, as one of the great stories of western tradition. But more broadly, this series is about our present cultural moment.

New Atheism seems largely to have faded away. In its place, we have a combination of steady Christian decline – happening at varying speeds in different western countries – with a search for alternative sources of meaning. Amongst these, one could point to ‘wellness’, self-help, and a range of online sub-communities interested in everything from masculinity to conspiracy theories.

‘Wellness Wheels’ are often used to represent the holistic aspirations at the heart of the wellness movement.

I thought about all this quite a bit while writing my next book The Light of Asia, due out in January 2024. Asia, it turns out, has often been the vantage point from which modern westerners have thought about what might or might not be ‘true stories’ back home: religious ideas, political ideologies, scientific claims about the world and much more besides. They found that to step away from the culture of their birth, and either travel to Asia or read about it – Japan and India in particular – gave them a fresh, often fascinating perspective on how their own society had been developing.

You might, at this point, be waiting for a working definition of ‘true story’ – insisting, in the face of that classic Simpsons episode, that you can handle the truth.

This series won’t work like that. I’m going to come at this question from a few different angles, all of them related in some way to western fascination with Asia, and see where that leaves us by the middle of December. I’ll publish an essay roughly once per fortnight, beginning here with history and moving into scientific naturalism and evolutionary psychology, our emotions, culture and social media, meditation and prayer, and the world of myth and magic.

Stick with me, and I see some J.R.R. Tolkien and C.S. Lewis in your future…

We historians love to talk about stories. You’ll often find us pointing out that modern nations are founded on the stories they tell about themselves: origins, values, purpose in the world. I called one of my books Japan Story for just that reason. I wanted to explore modern Japanese attempts to forge an identity and place for themselves in a modern world dominated by Western power.

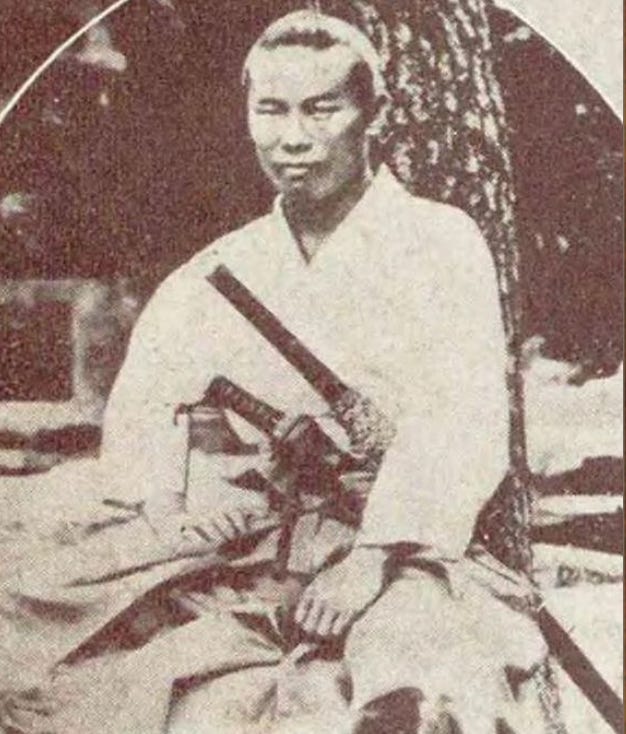

One of the best-known stories from the late nineteenth century was what we might call ‘Japan in danger’. The winners of a civil war in 1868-9 claimed that Japan was threatened by economically and militarily powerful western nations. The Tokugawa shogunate, which had ruled Japan since the early 1600s, had, they said, proven itself unable to meet these profound and urgent challenges. Instead, they – young samurai like Itō Hirobumi and Ōkuma Shigenobu – were going to sort things out.

Itõ et al made expedient use of the Emperor, as part of their storytelling. They wove him into a tale of restored imperial power and dignity, redeeming long decades of failure under the Tokugawa shogunate. Still just a teenager in 1868, the Emperor was plucked from obscurity behind palace walls in Kyoto and toured around the country to help reinforce the new story. Japan’s new capital, Tokyo, became his permanent home.

Storyteller extraordinaire: Itõ Hirobumi as a young man

‘Japan in danger’ was, by and large, a success. A population that had barely heard of the Emperor in 1868 fell to its knees outside the gates of Tokyo’s Imperial Palace a little over forty years later, mourning the Emperor’s death in the summer of 1912.

In what sense was this story ‘true’?

For a start, it could never have got very far unless elements of it resonated deeply with the intended audience – in terms both of who the Emperor might be and the kind of trouble that Japan was in.

It’s difficult to know how many Japanese in that era really believed in the divine ancestry that the imperial family claimed for itself, or even how much most Japanese thought about the question. The Emperor had been a somewhat remote figure over recent centuries.

Many people did believe, however, in the idea that kami (gods) populated their world and the world beyond. Japanese writers in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries can be found trying to persuade their compatriots to abandon ‘superstition’, and to adopt what we now call scientific materialism or naturalism: the view that reality is no more or less than matter in motion, ‘stuff’ shaped by physical laws.

One might only have a rather hazy sense of the kami, but the imperial family’s claimed kinship with them would be hard – for most – simply to reject. A certain reverence was called for.

The Sun Goddess Amaterasu, from whom Japan’s imperial family claimed descent.

It helped that ideas about the kami and the imperial family were powerfully reinforced in schools, in government rituals, in the media and at shrines, and also that the government’s broader story about Japan – it must preserve its sacred character in difficult geopolitical times – seemed plausible and urgent. Massive global change was clearly afoot, and Japan’s new leadership appeared to be meeting those challenges: by opening up to Western trade and diplomacy and by drawing on foreign examples to modernise Japan’s economy, military and politics.

Most historians regard it as our job to assess the truth of a story like ‘Japan in Danger’ by working with the available sources. We might look at global economics and politics, and the colonial mindset in Europe, and conclude that – yes – Japan was in danger. When it comes to the kami, we would employ a kind of methodological agnosticism. In the absence of anything that might serve as evidence, we focus instead on the human aspects: what people seem to have believed, where those beliefs came from, and what sorts of change they contributed to.

That is our vantage point: we choose our frame – Japan, in a particular period – and we trace a human scenario playing out over time.

Some historians will zoom out a bit, and ask how Japan’s new leaders came to be in a position to tell their ‘Japan in Danger’ story in the first place. In 1853, the American Commodore Matthew C. Perry arrived off Japanese shores with his infamous ‘black ships’ – so called for their dark hulls and smokestacks – and demanded, on behalf of his President, that Japan open itself up to trade and diplomacy. Cue a few years of heated, sometimes bloody internal debate in Japan, about how to respond to this challenge. The argument – and the war – was won by young, modernising samurai like Itō.

One of the infamous ‘black ships’.

Historians could zoom out further still, and suggest that Itō and co. did not so much cope with great winds of global change as find themselves blown into their leadership positions by those winds, and then buffeted along. Perhaps the imbalance of power between Japan and much of the West at this point was so great that had the arguments of this era not been won by a modernising faction, similar arguments would have forced themselves on Japan a few years or decades down the line.

This is about as far as you’ll find most historians willing to go. We’re cautioned not to assume the inevitability of a particular course of events, and never (or only in private) to indulge in counterfactuals – speculation about alternative paths that history might have taken.

It’s bracing, then, to find non-historians weighing in, and supplying alternative vantage-points. The writer Paul Kingsnorth is a case in point. In his essay, ‘Come the Black Ships’, he writes about the opening of Japan to Western trade and diplomacy as an example of the malign activity of what he calls the Machine: a ‘nexus of power, wealth, ideology and technology’ that has emerged to ‘rebuild the world in purely human shape’.

I was intrigued to find Kingsnorth all but investing trends in human affairs with personality and intention, here. I imagined the Machine as a steam-punk monstrosity of the kind found in Hayao Miyazaki films: rolling along, tank-like, belching smoke and bursting its rivets, crushing the natural order under its tracks.

Underpinning this notion of the Machine seems to be the idea, raised elsewhere in Kingsnorth’s essay series, that we overestimate the role of human beings in how history plays out and in how stories get written. Kingsnorth comments, at one point, that he is tempted to agree with Oswald Spengler (author of The Decline of the West [1918]) that there can be such a thing as a ‘story [that] emerges from the Earth and then creates a people to tell it.’

It's an intriguing idea, because it flies in the face of what we usually think about as being a ‘story’: a narrative that gives shape to a series of events, whether that be the ‘Japan in Danger’ narrative that Itō helped to sell to the Japanese, or books written by people like yours truly, seeking to make sense of a country’s history.

The notion that human beings might – sometimes, at least – more accurately be imagined as characters in a story, rather than authors, is not as far outside a historian’s purview as you might imagine.

In 2000, the historian Conrad Totman noted in his History of Japan that human beings ‘have not been trampling the daisies of this Earth for very long’. For the majority of that very short time, he went on, our ancestors’ lives were shaped profoundly by the biosystems of which they were a part. You might almost say that they were the instruments of those biosystems.

Only as little as 10,000 years ago did ‘human-centered biological communities’ arise, making a mark on the landscape with settled agriculture, animal husbandry, violent displacement of competitors and eventually industrial-age interventions in nature. Totman proceeded to give an account of Japan’s history that brought to the fore the shaping power of the natural environment, in every age.

A blade from Japan’s Yayoi era (c. 500 BCE - 250 CE), a regular feature of which seems to have been violent conflict between rival chiefdoms.

I found Totman’s book a frustrating read, the first time around. It seemed illegitimate, not to mention a bit boring, to banish human beings so far to the margins of Japan’s history. But more and more, I appreciate his attempt to widen the frame. It shows how the truth of a story depends deeply on the perspective that we take.

Plenty of Japanese in the late nineteenth century believed – you could say ‘lived inside’ – Itõ’s ‘Japan in Danger’ story. And they weren’t wrong. It must have felt vividly true, and even from the outside – for historians writing in the twenty-first century - it seems to have had much truth to it.

Equally, though, the Kingsnorth story – let’s call it ‘The Rise of the Machine’ – may also be true, from its own perspective. This moment in Japanese history can be thought of not so much as a political debate, where lots of options were on the table, as the inevitable triumph of technology and capital. Totman’s environmental story in fact merges in places with that of Kingsnorth, who has a background in environmental activism.

To argue for multiple perspectives is not to argue for relativism. It is more about noting the impossibility – even in principle – of a complete or absolute point of view on any given set of events. Take some time with this idea, and you might find that it brings you up against the limits of your thinking and imagining.

This may well be true not just for history, but for the ‘facts’ of our everyday existence. Which brings us to another sort of story altogether. For all that New Atheists like Richard Dawkins attracted critics amongst philosophers and theologians, he was asking a very good question: what exactly are we doing when we tell religious stories, or use religious language?

I’m going to get to this next time, in New Atheism – Goodbye to All That?

—

Images:

‘Wellness Wheel’: University of Nevada, Las Vegas (fair use).

Gandalf: LitHub (fair use).

Itõ Hirobumi as a young man: National Diet Library of Japan (fair use).

Amaterasu: Mythopedia (fair use).

Black ship: MIT Visualizing Cultures (fair use).

Yayoi-era blade: World History (fair use).