Thank you to everyone who completed my poll on how often you’d like a fresh IlluminAsia post and what you’d like me to cover. No-one voted for a two-month gap, so apologies for the hiatus these past weeks. Up and running again now and I’ll be aiming to write something worthy of your time around once per month.

Amongst the projects that have kept me away from these pages are two that involve influential books with major anniversaries this year. The first is Aldous Huxley’s The Doors of Perception, about which I’ve written a short essay for Engelsberg Ideas. Now seventy years old, it’s an account of the Brave New World author’s experiment with a psychedelic called mescaline.

I remember reading The Doors of Perception as a teenager and being intrigued by Huxley’s claim - made by others before him and since - that the brain doesn’t so much produce consciousness as filter it. It does so, he claimed, on the basis of our basic needs: for safety, sustenance and passing on our genes. Aside from the Van Goghs and Bachs of this world, few of us are granted a more expansive vision. And yet as William Blake, the inspiration for Huxley’s title, put it:

If the doors of perception were cleansed, everything would appear to man as it is, Infinite. For man has closed himself up, till he sees all things thro' narrow chinks of his cavern.

Huxley was right up my street as a boy for all sorts of reasons. I was brought up a Catholic, had become interested in Japan and Buddhism, loved philosophy and respected the concept of evidence in disciplines like history and the sciences. Within the space of a decade, Huxley published two books which - for a while at least - seemed to hold out the promise of reconciling all these things.

The first was The Perennial Philosophy, in 1945. Huxley claimed that the world’s mystical literature, much of it from Asia, provides clear evidence of diverse religions and philosophies having shared roots in a taste of the same Divine, or Godhead.

Here, Huxley hoped, was a sound basis on which to build a postwar world. Treaties and trade agreements were all very nice, but they hadn’t had much success in keeping the peace. Persuade people, on the other hand, that their deepest instincts about themselves and the world are in alignment with those of others around them, and given time things might change.

Aldous Huxley, photographed in 1954

I found all this deeply consoling. First, because though I might have doubts about the details, my own Catholic tradition appeared at least to be getting at something. Second, because although my parents once called our attention to the no-doubt Protestant cars sitting idle in no-doubt Protestant driveways on a Sunday morning while us serious Christians zoomed off to Mass, I was never taught to look down on other religions. So I took comfort in Huxley’s assurance that what seem to be vastly different traditions may be responses to one and the same unfathomable reality.

Nine years later, Huxley held out the promise that this reality need not remain quite as dim and distant as I had supposed it must. He was cautious not to conflate mescaline with mystic vision, but he clearly saw them as close relations. Better still, he appeared to offer a scientifically plausible account of how both worked: the doors of perception are dirty by (evolutionary) design, but give them a wipe and light floods in.

An alternative interpretation of these ideas was that the brain produces consciousness and that the elevated states associated with austerities, meditation, prayer and psychedelics are reducible in the end to biochemistry. As advocates of this claim will tell you, not unreasonably: just because we don’t yet have an account of how the brain gives rise to consciousness doesn’t mean that it isn’t true.

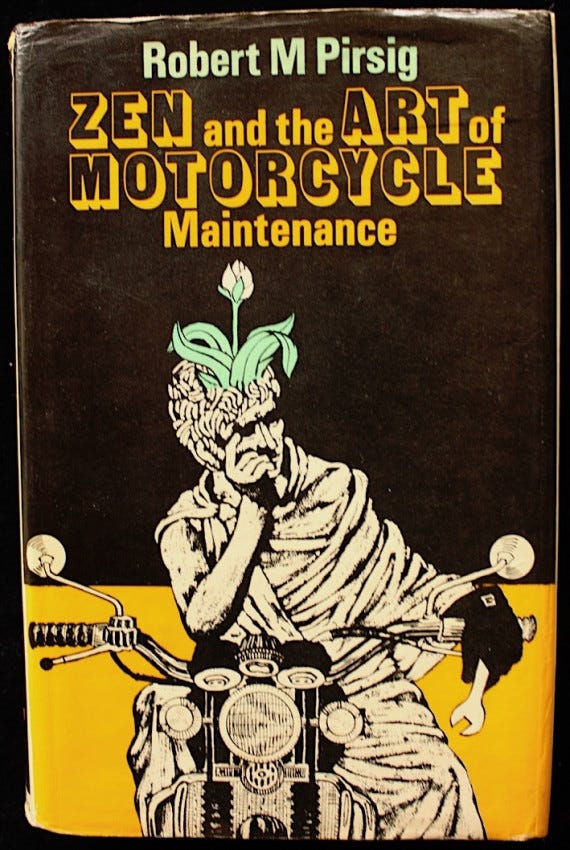

This is where book anniversary number two comes in. Robert Pirsig’s Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance was published in 1974, and was expected by its publisher to achieve cult status - in the sense of selling relatively poorly but being cherished by a niche crowd of zealous fans. Instead, it became a bestseller. Stories of the 121 publishers who turned down the manuscript became an echo of the record execs who said ‘Thanks, but no thanks’ to The Beatles.

Original edition published in Britain, 1974

Zen is a memoir of sorts, combining an account of a motorcycle journey taken by Pirsig and his son Chris with the story of Pirsig’s search for wisdom and its climax in breakdown, hospitalization and electroconvulsive therapy. Re-reading it for a documentary that we’re making for BBC Radio 4 (scheduled for broadcast on 18th May), it strikes me that it shares quite a bit with The Doors of Perception.

Both books are about how we might better relate to reality, beyond what Huxley called ‘verbal orthodoxy’ and Pirsig dubbed ‘classic formalism’. Both terms pointed to the common but - they believed - mistaken expectation that anything real can be put into words and anything that can’t be put into words cannot be real.

Equally false, as far as both writers were concerned, was the default assumption of their day that reality is ultimately matter in motion. Huxley believed in a Divine Ground or Godhead, from which everything flows. Pirsig, deeply indebted to Zen, Vedanta and Taoism, wrote about ‘Quality’ as a kind of transcendental value and the source of mind and matter alike.

Pirsig’s bike - a 1966 Honda Super Hawk - is now part of an exhibition at the Smithsonian in Washington DC: ‘Zen and the Open Road’

Many have been tempted to write off The Doors of Perception and Zen as mere products of their time: dispatches from either end of a counter-culture era that became notorious for combining shallow takes on Eastern wisdom, heavy use of psychedelics and suspicion of mainstream society and its standards. It all became a magnet for satire, though of the slightly debased sort that skewers an idea’s excesses or most eccentric advocates without actually confronting the claim itself.

That increasingly looks like a mistake. Psychedelics have been making a come-back of late, both in medical research into treating conditions like depression and amongst wisdom-seekers willing to fork out for a guided ayahuasca retreat. Meanwhile, amongst philosophers a range of theories are gaining ground that suggests mind may run deeper than matter. It also turns out to be harder than you might think to say what matter actually is.

If I had to pick a couple of heirs to Huxley and Pirsig’s projects, I’d go for the psychiatrist and writer Iain McGilchrist (author of The Matter With Things) and Jeffrey Kripal (The Flip). McGilchrist explores the role of the brain’s hemispheres in how we pay attention in the world, while Kripal is interested - amongst other things - in the power of things like near-death experiences to radically shift people’s instincts about what reality is like (this is what he means by undergoing ‘the flip’).

Neither writer offers a straightforward how-to guide for shifting our relationship to reality - and nor, for that matter, did Huxley or Pirsig. What I think all four offer instead is a set of sound reasons why the world might be stranger and richer than we imagine, invoking Asian philosophies and the farther reaches of scientific thinking in order to help make their case. For all that this combination might sometimes feel like a relic of a bygone era - The Tao of Physics hits its half-century next year - when it comes to forcing us to re-examine our worldview it still packs quite the punch.

—

Images:

The Doors of Perception, front cover: fair use.

Photograph of Aldous Huxley: public domain.

Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance: fair use.

Exhibition, ‘Zen and the Open Road’: fair use.

Since IlluminAsia posts have resumed after a hiatus, as a reader I would like to voluntarily remind everyone about Chris's recently published book The Light of Asia. It is available in a variety of formats. I bought the audio version and enjoyed it. On audible.com, The Light of Asia currently has two ratings at the time I submit this comment. I was the second person to rate it. Whether you buy The Light of Asia in audio or another format, I am confident that Chris would appreciate both sales and a positive rating.

https://www.audible.com/pd/The-Light-of-Asia-Audiobook/B0CDXSJ4S8

Hi, I am from Australia. I really like your website. I have done a browse on some of your essays.

Please find an introduction to a unique Philosopher & Artist whose first book was published in 1972.

Please check out these references

http://www.daplastique.com/essay/the-maze-of-ecstasy

http://beezone.com/2main_shelf/forward.html Alan Watts foreword to the 1972 book

http://www.kneeoflistening.com/forward Jeffrey Kripal's foreword to the 2004 edition of the above book

The authors very real Living Connection to both Hinduism & Buddhism

http://www.adidam.in/forerunners

http://www.adidaupclose.org/FLO/karmapa.html

http://beezone.com/1main_shelf/four_yanas_of_buddhismedit.html

Critical essays on Christianity

http://www.dabase.org/up-1-1.htm

http://www.dabase.org/up-1-2.htm A Prophetic Criticism of the "Great" Religions

http://www.dabase.org/up-6.htm The Spiritual Gospel of Saint Jesus of Galilee Retold

On the Miracle of "Matter" and Conscious Light

http://www.integralworld.net/reynolds16.html

http://www.integralworld.net/reynolds38.html