From a cave deep inside a Japanese mountain, a bolt of blinding laser-light shoots forth. It soars into the sky, disappearing into the clouds. Moments later, the centre of Washington DC is vaporised and its outskirts begin to burn…

Such were the bold imaginings in wartime Japan about how its conflict with the United States and Great Britain would ultimately be settled. Since as far back as the 1910s, Japanese science and scientists had been presented to the general public as guarantors of the nation’s future. Now, in time of war, the population was assured that Japan’s best and brightest were once again on the case.

Advertisement for a health-giving ‘Radium Parlor’ (1913), part of a medical and commercial campaign extolling the benefits of radium and radiation.

The reality, by mid-1945, was that Japanese citizens were being drilled in the use of bamboo spears, to defend the homeland against American GIs who were expected any day. Desperately short of fuel and matches, Okinawans had taken to reading at night by the light of phosphorescent sea creatures.

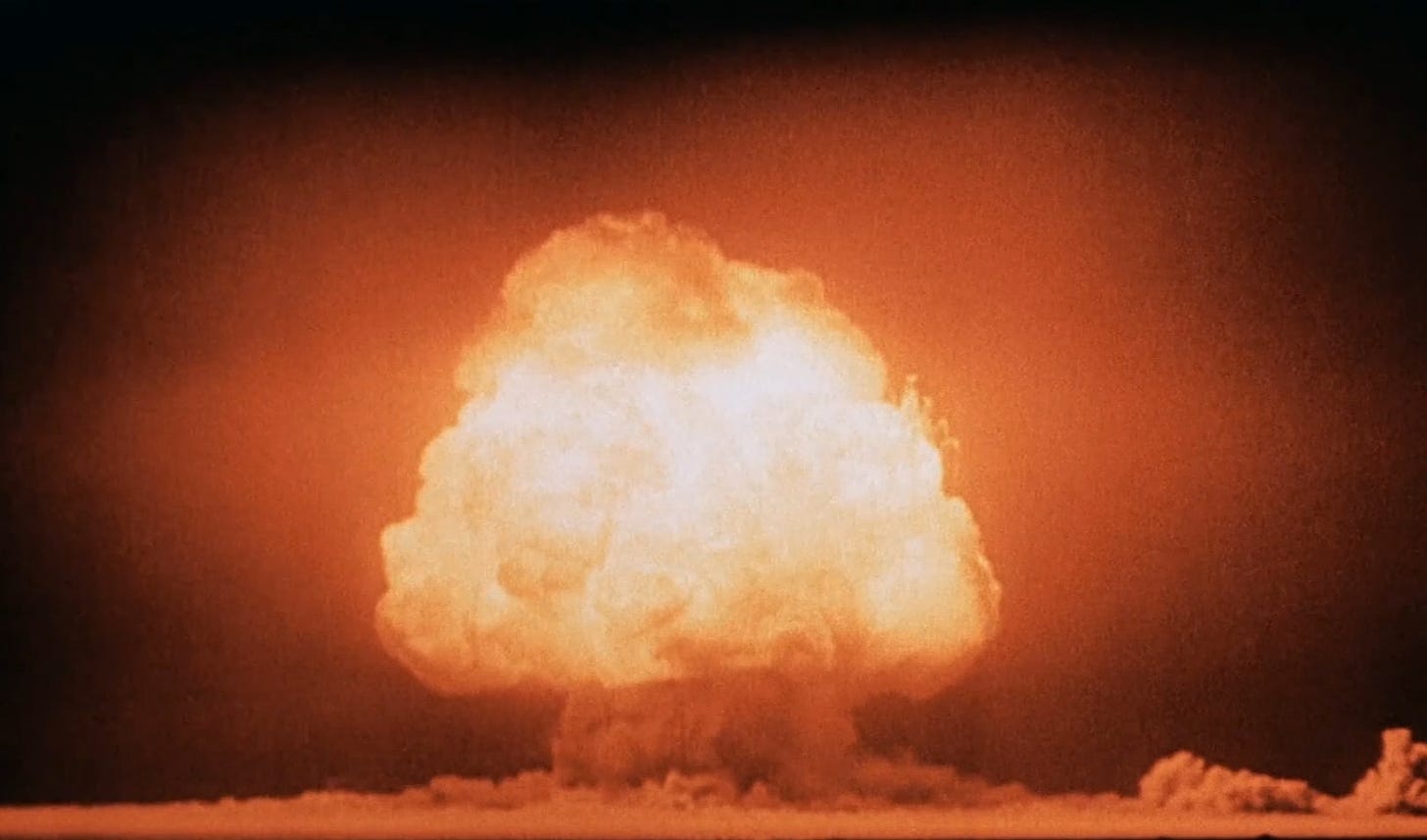

The race to out-invent the enemy was being won not in Japan but about 6,000 miles to the east, on the Los Alamos plateau in New Mexico. The nuclear physicist J. Robert Oppenheimer was leading a team charged with developing an atomic weapon. On 16th July 1945 the Trinity test took place: the world’s first nuclear detonation.

The ‘Trinity’ test, 16th July 1945

Oppenheimer later claimed that as he watched the explosion some lines from an ancient Indian scripture, the Bhagavad Gita (Song of the Lord), had come to mind:

If the radiance of a thousand suns were to burst at once into the sky,

That would be like the splendour of the mighty one…

Now I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds.

Whether or not Oppenheimer really thought these things at the time, or inserted them later into his memories of that moment, he was not just reaching for a grandiose phrase, attempting to do justice to a turning-point in history.

For years, the Gita - an extended conversation about how to live, between a prince named Arjuna and Lord Krishna - had given Oppenheimer a poetic, even mystical foundation for his attempts to live a purposeful, disciplined life.

The Gita was, thought Oppenheimer, ‘the most beautiful philosophical song existing in any known tongue’ - this from a man who had read it in the original Sanskrit.

Scene from the Bhagavad Gita, showing Arjuna and Krishna in conversation

Oppenheimer’s interest in the Gita placed him in a long tradition of Westerners looking to Asian wisdom for inspiration, and motivations had always been mixed.

The first person to translate the Bhagavad Gita into English, in 1785, was Charles Wilkins: an employee of the East India Company, which at this point was beginning to expand its political and military control over the subcontinent - laying the foundations for the British Raj.

Wilkins’ boss, Governor-General Warren Hastings, was both a lover of Indian literature and a ruthless pragmatist. ‘Every accumulation of knowledge’, he noted, in a letter published as a preface to Wilkins’ translation, ‘is useful to the state’.

As interest in Asian wisdom gathered pace, westerners hoped that it might breathe fresh life into their own rather desiccated religions and philosophies.

Some found, in aspects of Indian and Chinese thought, an Asian Stoicism. Others, including Goethe and Samuel Taylor Coleridge, fell in love with the grand and consoling Idealism of the Upanishads. In these revered spiritual commentaries could be found the idea that beyond the chopped-up chaos of everyday experience - regarded as māyā, or ‘illusion’ - the cosmos is a benevolent, glorious whole.

In the United States, Ralph Waldo Emerson and his Transcendentalist Club were amongst the first to try to tap the potential of Asian thought. Emerson warned an audience at Harvard in 1838 about confusing real, living religion with the monarchical, formulaic kind - which too many American priests and ministers were foisting on their dwindling flocks. ‘I look for the hour’, cried Emerson, ‘when that supreme Beauty, which ravished the souls of those eastern men… shall speak in the West also.’

By the time that Oppenheimer came to study Indian literature, in the 1920s and ‘30s at Harvard and Berkeley, the ‘decline of the West’ was a well-established theme amongst anxious intellectuals. They pointed to the waning power of Christianity to compel people - spiritually, morally, imaginatively - and to the devastation of the Great War as a sign of where decline could lead.

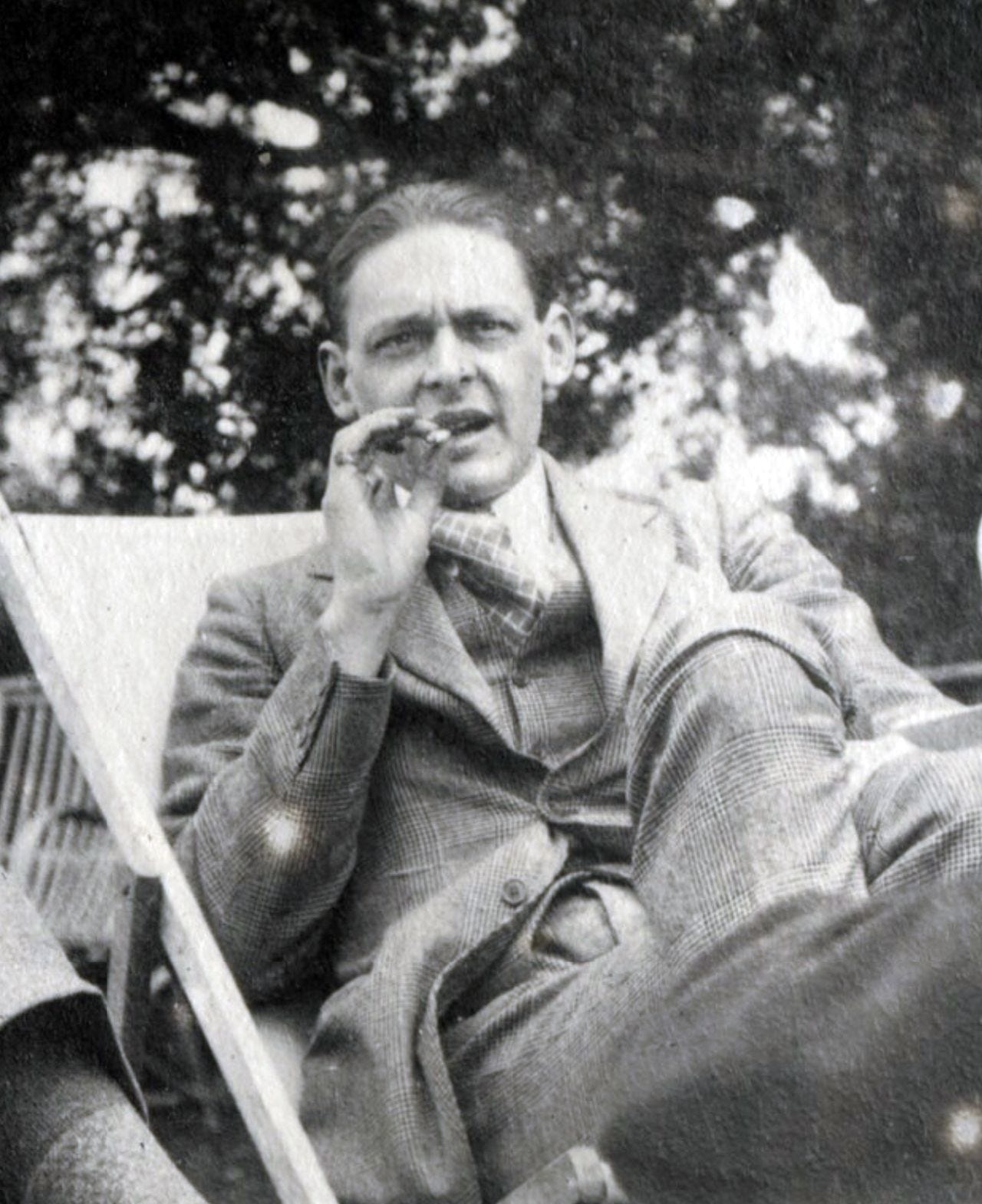

One of the great poets of this dark moment was Oppenheimer’s fellow Harvard alumnus, T.S. Eliot. Like Oppenheimer, Eliot studied Indian languages and literature at Harvard, reading the Gita in Sanskrit and declaring that India’s sages made ‘most of the great European philosophers look like schoolboys’. Eliot ended his poem The Waste Land (1922) in the manner of an Upanishad: with the Sanskrit mantra ‘shantih, shantih, shantih’.

T.S. Eliot (1888 - 1965)

As Coleridge had done before him, Eliot eventually turned away from Indian thought and towards Anglicanism. But he held onto the Gita’s advice about working without attachment to the fruits of your labour - refusing to hug desires, or cling to goals:

And do not think of the fruit of action.

Fare forward....

So Krishna, as when he admonished Arjuna

On the field of battle.

Not fare well,

But fare forward, voyagers.

[‘The Dry Salvages’, from Four Quartets (1943)]

Oppenheimer once placed Eliot’s The Waste Land alongside the Gita as two of the ten works of literature that had most influenced him in his life. And like Eliot, he was moved by the ideal of living and working in the right way without hoping for particular results. Oppenheimer found a strikingly similar idea in Shakespeare’s Hamlet: ‘Our thoughts are ours, their ends none of our own’ [Act 3, Scene 2].

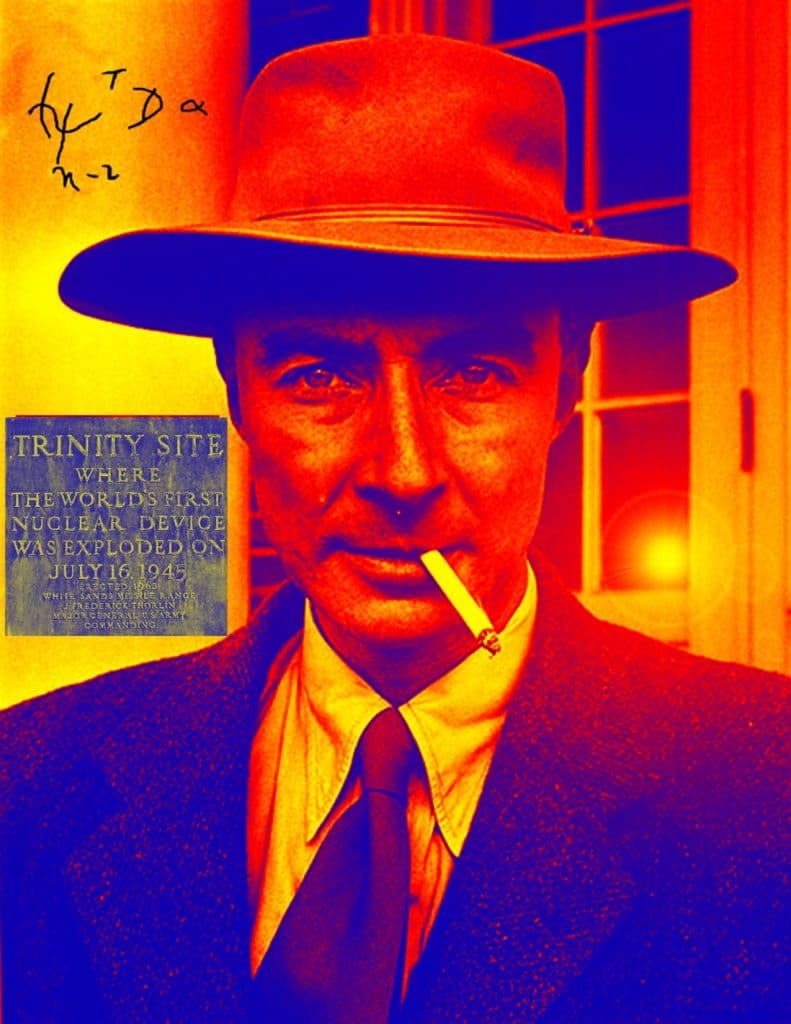

For Oppenheimer, this non-attachment to outcomes was part of dharma: a concept loosely translatable as ‘righteousness and duty’. Each person had their own dharma, and Oppenheimer saw his as his scientific vocation - specifically, his work on the Manhattan Project.

Fond of quoting Indian scripture to others on the Manhattan Project, Oppenheimer urged his colleagues not to consider too deeply the fruits of their labour - in other words, the uses to which an atomic weapon might be put.

Their dharma was to build the bomb. When or how to deploy it - that was someone’s else’s.

This was not Oppenheimer’s way of washing his hands of atomic weapons. He was all in favour of their use - believing, as many did, that the bomb was the best way to end the war against Japan with the minimum loss of life on all sides.

Oppenheimer refused to advise that the bomb be used on any target other than a city. Anything else, he argued, would be seen by Japan’s leaders as a mere ‘firecracker over a desert’.

J. Robert Oppenheimer (1904 - 1967)

Oppenheimer’s quoting of the Gita was not the only means by which Asian wisdom made it into World War II. Keen to show its loyalty to the state, Japan’s Buddhist establishment vigorously supported the conflict. Buddhist clergy offered Zen meditation retreats for army officers and published philosophical musings on the justness of the war - a Buddhist, it was often said, might take a person’s life if it prevented them from accumulating bad karma later on.

Where the Trinity test put Oppenheimer in mind of the Gita, those who survived the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki recalled Buddhist images of hell.

There was simply no other way to make sense of the flaming streets, the buildings igniting all around them and the sight of people walking along, bewildered, as their flesh dropped off them into the soft, bubbling asphalt. Blistered and bloated figures lay everywhere around them, mouths filling up with maggots and flies.

From Iri and Toshi Maruki’s ‘Hiroshima Panels’

For a while after war’s end in 1945, it was thought that only a coming together of ‘Eastern’ with ‘Western’ wisdom could help prevent human beings from destroying themselves, now that they possessed the means to do so. By the time that Oppenheimer passed away in 1967, that promise seemed - to some, at least - to be on the verge of fulfilment.

To find Indian wisdom in the mouth of a Harvard-educated nuclear physicist was one thing. To hear it on a Beatles record was something else entirely. 1967 was the year of Sgt Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, which included George Harrison’s song ‘Within You Without You’ - heavily indebted to Indian music and spirituality. Sailing the Aegean on holiday that summer, Harrison had the Beatles chanting ‘Hare Krishna’ aboard their boat, late into the night.

It had been part of Oppenheimer’s view of the world that the ultimate outcome of Hiroshima and Nagasaki - with luck, humanity’s turning-away from war - would not become clear in his lifetime. The same may be true of Asian wisdom’s long and ongoing journey westward. The Sixties feel like another world now. But there is something about the image of George Harrison reading the Gita to his mother on her deathbed, as he is said to have done, that suggests a willingness to be open to, even intimate with new views of the world. Reason, perhaps, for a little hope.

American service personnel assessing the aftermath at Hiroshima

—

Suggested Reading:

Maika Nakao, ‘Radium traffic: radiation, science and spiritualism in early twentieth-century Japan’, Medical History 65 (2021)

Dorothy M. Figueira, The Afterlives of the Bhagavad Gita (Oxford University Press, 2023)

James A. Hijiya, ‘The ‘Gita’ of J. Robert Oppenheimer’, Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society 144/2 (2000)

Jeffrey M. Perl & Andrew P. Tuck, ‘The Hidden Advantage of Tradition: On the Significance of T.S. Eliot’s Indic Studies’, Philosophy East & West 35/2 (1985)

K.S. Narayana Rao, ‘T.S. Eliot and the Bhagavad-Gita’, American Quarterly 15/4 (1963)

Christopher Harding, Japan Story: In Search of a Nation, 1850 to the Present (Allen Lane, 2018)

—

Images:

‘Radium Parlor: Maika Nakao, ‘Radium traffic: radiation, science and spiritualism in early twentieth-century Japan’, Medical History 65 (2021)

Nuclear test on 16th July 1945: United States Department of Energy (public domain).

Scene from the Bhagavad Gita: Sivananda Yoga Vedanta Center (fair use).

‘The Bhagvat-Geeta’: Creative Commons (public domain).

T.S. Eliot: Creative Commons (public domain).

J. Robert Oppenheimer: Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists (fair use).

Iri and Toshi Maruki’s ‘Hiroshima Panels’: Pioneer Works (fair use).

Assessing the aftermath at Hiroshima: Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists (fair use).