Life can be hard for Japanese ex-pats living in the UK. Unpredictable weather. Unpredictable trains. Shops where, unless you’re parting with serious money for high-end fare, there is - to put it mildly - no guarantee of encountering a customer-is-king outlook.

For my wife, who hails from sun-drenched Okayama, one of the hardest things to get used to was the supermarket. Beef mince that’s grey on the bottom. Fresh fish selections where the odour suggests ‘not fresh’, and there isn’t much of a selection.

Personally, I’ve never been much of a gourmand. Most of the fish I ate prior to living in Japan was the magically-breadcrumbed species, and one of the first UK sights I chose to show my wife was Pizza Hut (it’s a miracle she stayed). But still, I feel embarrassed for Blighty.

Losing out to Japan on the price and quality of fresh fish - at least in parts of the UK where it has to do a good few miles between sea and supermarket - is something I can live with. And thanks to the miracle of soy sauce, even so-so-raw salmon is alright for making salmon and avocado rice (if you’re worried about turning your insides into a parasite’s paradise, you can freeze the salmon first).

But to be bested by Japan on beef? That seems perverse. It’s been on the menu in Britain for centuries - we are, let’s not forget, les rosbifs. Japan, meanwhile, only put aside its beef with beef 150 years ago.

British satirist James Gillray mocks the French Revolution, suggesting that Brits were doing alright out of monarchy (December, 1792).

The people of the ancient archipelago hunted as well as fished. But soon after the arrival of Buddhism in Japan, in the sixth century CE, a taboo set in against eating four-legged animals.

Beef and milk were thought to have medicinal benefits, so a small amount was consumed on that basis. But fire up the barbecue and you risked finding yourself on the menu in the next life. Cattle were instead used in Japan primarily as farm labour, and for transporting heavy goods from place to place.

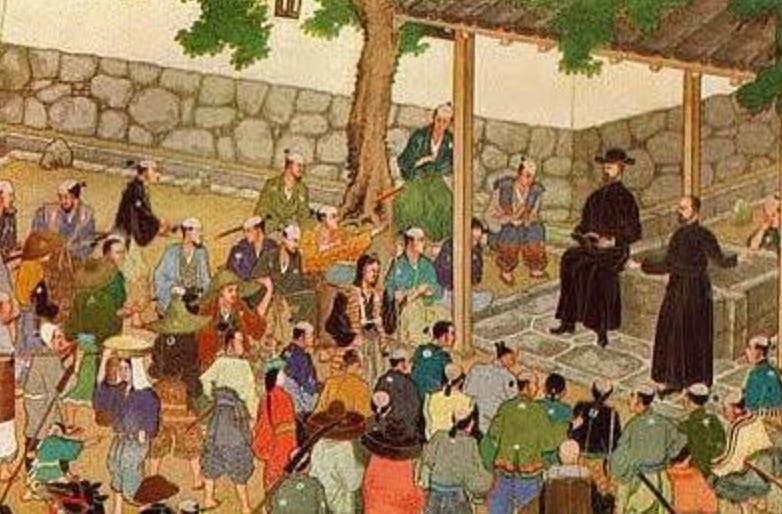

Meat-eating struck people not just as immoral but also as a little uncouth. When Jesuit missionaries began arriving in Japan in the mid-sixteenth century, in the company of Portuguese traders, the country’s lordly elite found it hilarious that Europeans would presume to preach to them about the glories of heaven while keeping filthy farm animals under their roof - eating their flesh, and drinking their milk.

Above: a folding screen (byōbu) showing a party of Portuguese traders arriving in Japan in the late 1500s. This group also features Malays and enslaved Africans.

Below: Jesuit missionaries preaching to a group of Japanese, just beyond what look like the walls of a castle.

The association between cows and Christianity never fully went away. In the late nineteenth century, some Japanese Christian converts described arrogant or overbearing western missionaries as bata-kusai: ‘stinking of butter’. They were angry at the missionaries’ insistence on defining ‘Christianity’ in terms of Western culture and standards - which some wag managed to connect with an unusual fondness for dairy products.

But times were changing. When Japan opened its doors to renewed contact with the West in the mid-nineteenth century, Japanese leaders were horrified at their country’s vulnerability. Mostly this was a technology gap: Japan lacked such military essentials as steam-powered warships and rapid-fire artillery.

And yet attention was paid not just to what western troops fought with, but also what they ate. The apparent ability was quickly noted of a beef-rich diet to build up soldiers’ bodies and to speed the recovery of those injured in combat.

Beef was duly placed on the menu in the barracks of Japan’s new Imperial Army, from the late 1860s onwards. Ten years later, the chance to try various beef dishes was amongst the many extraordinary things that one could see and do in the rapidly-modernising city of Edo, which had recently been re-named ‘Tokyo’ - Eastern Capital.

Just one of many extraordinary sights in Japan’s rapidly-modernising capital: a steam train, running from Tokyo out to Yokohama. (‘Steam train between Tokyo and Yokohama’, by Utagawa Hiroshige III, 1875).

Japan’s beef boom nearly didn’t happen. After the samurai class was abolished in the early 1870s, a few former samurai tried their hand in business instead. Some were very successful, but clearly not everyone had the knack for it. Newspapers were soon full of gleeful accounts of bushi shōhō, or ‘warrior business-management’: new ventures swiftly driven into the ground by uppity and incapable ex-samurai, struggling with their loss of status.

Those involved in supplying and serving beef became notorious for seeking to rig prices and for having little interest in quality-control. Barely a generation earlier, they could have put a commoner to the sword for some minor slight. Why worry overmuch about their health now?

But plenty of Tokyoites were interested in finding out whether meat was indeed one of the ingredients of Western success. In Western-style restaurants, self-satisfied ex-pats were treated to the sight of Japanese friends inexpertly wielding knife and fork, chasing a piece of meat around their plate.

In some of the rougher outlets, meanwhile, true culinary magic was being wrought. Beef was marinaded in flavours like soy sauce and miso, and then fried or stewed before being served up to customers bunched tightly together in cramped, steamy spaces.

People tucking into ‘gyū-nabe’ (beef hot-pot)

By 1877, Tokyo was home to no fewer than six hundred so-called ‘stew restaurants’, and enterprising companies were soon helping people to recreate their extraordinary dishes at home. The Emperor himself was said to be a fan of beef - prompting, on one occasion, a group of Buddhist monks to try to break into the Imperial Palace and dissuade him.

Cattle began to be imported into Japan, and cross-bred. Much the same happened with menu ideas, and by the end of the twentieth century ‘Wagyu’ - literally ‘Japanese beef’, but denoting specific cattle breeds - came to be associated internationally with very high-quality meat.

It was a matter not just of tenderness and taste but also the aroma given off while the relatively high-fat meat is being cooked - heightening the enjoyment of sukiyaki and shabu-shabu dishes, where the meat is cooked at the table.

Most of the beef eaten in Japan is not Wagyu - even in its native land it’s not cheap. But the quality of ordinary beef, plus the flavours used to cook it - from miso through to a sugary saké called mirin - mean that even at good-old Yoshinoya, one of Japan’s big fast-food chains, you’ll still get a (reasonably) tasty bite to eat.

Japan’s Yoshinoya chain, founded in 1899, has its roots in Tokyo’s Meiji-era beef boom

Vegetarians need not despair entirely. Japan has more to offer now than ever, especially in its big cities - tempura, tofu dishes, and lots more besides. You can also try shōjin ryōri: traditional, plant-based Buddhist cuisine of the kind that the men who broke into the Imperial Palace were seeking to urge on their emperor. Temples in Kyoto are a good place to find it.

It isn’t easy, though. A century and a half after re-embracing meat, Japan is an enormously meaty place. As a source of animal protein, it overtook fresh fish and shellfish back in 2007. Perhaps environmental concerns will start to reverse that trend soon, especially if cultured meat takes off - recently championed by Japan’s Prime Minister, Fumio Kishida.

In the meantime, westerners have of course been going wild for sushi. Why? How? All will be revealed next week in Part II of Surf vs Turf - ‘The Surf Strikes Back’...

Above: ‘What kind of restaurant makes you cook your own food?’ Scarlet Johansson and Bill Murray fail to enjoy shabu-shabu, in the 2003 film Lost in Translation. Thin slices of raw beef can be seen in the foreground, ready to go into the broth.

Below: a shabu-shabu set just waiting to be enjoyed…

—

Suggested Reading:

Naomichi Ishige, The History and Culture of Japanese Food (Routledge, 2001).

Sasaki et al, ‘Meat Consumption and Consumer Attitudes in Japan: An Overview’, Meat Science (October 2022).

Motoyama et al, ‘Wagyu and the factors contributing to its beef quality: A Japanese industry overview’, Meat Science (October 2016).

Christopher Harding, Japan Story: In Search of a Nation, 1850 to the Present (Allen Lane, 2018).

—

Images:

French and British cuisine: Met Museum (public domain).

Folding screen: Museum with No Frontiers (fair use).

Jesuit missionaries preaching in Japan: RekishiNihon (fair use).

Steam train between Tokyo and Yokohama: MIT Visualizing Cultures (fair use).

‘Gyū-nabe’: Kome Academy (fair use).

Yoshinoya: Yoshinoya.com (fair use).

!["Steam train between Tokyo and Yokohama" by Utagawa Hiroshige III, 1875 [2000.549] Sharf Collection, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston "Steam train between Tokyo and Yokohama" by Utagawa Hiroshige III, 1875 [2000.549] Sharf Collection, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F540b76c5-8fcf-41ac-a122-ed867aad3888_1299x650.jpeg)

![Osaka] 10 Restaurants for Shabu-Shabu and Sukiyaki in the Namba and Umeda Area Discover Oishii Japan -SAVOR JAPAN -Japanese Restaurant Guide- Osaka] 10 Restaurants for Shabu-Shabu and Sukiyaki in the Namba and Umeda Area Discover Oishii Japan -SAVOR JAPAN -Japanese Restaurant Guide-](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F609e51cb-d6aa-4202-a272-326816c02f3d_640x480.jpeg)