When the American Commodore Matthew C. Perry arrived off Japan’s shores in 1853, demanding diplomatic relations at the point of a gun, Japan was thrown into a crisis. But the Tokugawa shogunate had been around since the early 1600s, and knew a thing or two about holding onto power. Its gambit in the late 1850s and 1860s was to forge foreign friendships that might secure Japan’s security, and their own position at the helm.

Embassies were duly sent westwards, to the United States in 1860 and to Europe in 1862. A photograph of the US embassy gives a vivid sense of a Japan as-yet largely untransformed by contact with modern western culture. Top-knots, sandals, silk kimono and swords - all these things would be gone within twenty years of this photograph being taken.

Japan’s ‘samurai embassy’ in the United States, 1860

Diary entries written by members of the embassy reveal surprise that the United States lacked a great ruling dynasty like the Tokugawa family - why were the Washingtons, descendants of America’s first president, not still in charge? And why was the food so awful?

‘Greasy soup with saltless small fish’ was bad enough. But the crimes against rice were far worse. Tasteless grains, fit only for Japan’s poorer classes, were served up - in some cases cooked in butter or sugar. Some of the samurai chose to go hungry, enduring ‘hardship [that] cannot adequately be described with a pen’.

Lesson learned, when an embassy set sail for Europe in 1862 it did so with hundreds of cases of rice aboard, together with all sorts of other provisions.

Ten years later, everything had changed. The shogunate had gone, vanquished in a civil war (1868-9) whose winners were set on modernizing Japan along Western lines. That included food, with Japan’s (re)conversion to beef only the first step in a wide-ranging culinary encounter.

Tokugawa forces, pictured in c. 1867

In the final two decades of the nineteenth century, and with the support of the new government after 1868, increasing numbers of Japanese began to seek their fortunes abroad. Many went to Hawaii, while others made homes on the west coast of the United States. And it was here, after the incursion of turf into Japan, that surf began to strike back.

The first Japanese-owned restaurant to serve Japanese food in the United States was ‘Yamato’, which opened in 1887 in San Francisco. Most of these early Japanese restaurants offered a beef and vegetable stew called sukiyaki - it hadn’t taken long for the export of beef-eating to Japan to come full circle, back to the West.

In 1921, what may have been the first American restaurant to sell sushi - Matsu no Sushi - opened its doors in Los Angeles. Immigration restrictions and World War II put the brakes on American enthusiasm for sushi for a while. But from the mid-1960s, both sushi and sashimi started to take off in New York and California.

Sushi has its origins in China, or perhaps South-East Asia - it depends who you ask - and probably made it to Japan along with rice at some point in the second or first millennium BCE. The word itself, ‘sushi’, perhaps comes from the Japanese word sui, meaning sour-tasting - many early Japanese recipes for sushi were indeed sour, as a result of lactic-acid fermentation (a process used to preserve fish for longer).

For centuries, sushi created in this way was an elite food, made with fish including sea bream, mackerel and salmon, and appearing on the tables of imperial aristocracy and samurai. It wasn’t always eaten with rice, but from the fifteenth century this became more common. Presentation mattered hugely, and the best sushi chefs were known as hōchōnin: ‘masters of the (carving) knife’, who could cut the fish in just the right way.

A ‘Master of the Knife’, from ‘Poetry Contest by Various Artisans’ (c. 1500)

One could appreciate a hōchōnin’s dexterity even while regarding cutting, and blades in general, as inauspicious (not least because of the association with severing ties - never give a knife or a pair of scissors as a wedding present in Japan). For this reason, the euphemism ‘sashimi’ was used to refer to raw - and unfermented - fish once it joined sushi on Japanese menus in the late medieval era.

Archaeologists whose happy task it is to dig out ancient toilets and test for parasites have suggested that raw fish was eaten in Japan many centuries before. But only in the 1400s does it start turning up in texts on food preparation.

Into the early modern era, saké and later vinegar were used to speed up the fermentation process - creating ‘fast sushi’ (hayazushi).

Makizushi dates from this time, too: ‘sushi rolls’, created by wrapping rice and other ingredients inside pieces of dried seaweed (nori), became popular in the late 1700s. Vinegar was increasingly used, from this time on, to flavour the rice, too.

Makizushi, part of ‘Bowl of Sushi’ by the artist Hiroshige (1797 - 1858)

By the dawn of the twentieth-century, sushi had become Japan’s answer to fast food, sold at street stalls in big cities like Tokyo. A person looking for a sit-down bite to eat would have the choice of many hundreds of beef ‘stew restaurants’ by this point, but only a handful of sushi restaurants. By 1926, there were more than 3,000 sushi restaurants in Tokyo. Another quarter-century later, in the 1950s, the first kaitenzushi shops - serving sushi on a conveyor belt - opened their doors.

Most of sushi’s ‘early adopters’ in the West, in the 1960s, were linked to the counter-culture - they had either been to Japan, on their travels, or were hungry for something a little exotic. That changed a decade later, when Americans first started to get worried about processed food. Fresh fish - whose preparation by chefs you could actually witness for yourself - started to be in serious demand.

The 1970s were the take-off decade for sushi in Europe, too. London had long been home to Japanese restaurants, thanks to a large Japanese population (the same was true for Peru and Brazil, for the same reasons). The Netherlands got its first Japanese restaurants in 1971 - ‘Toga’ and ‘Yamazato’ - and many more followed across Europe, catering primarily to the ever-larger number of businessmen that Japan’s booming industries were sending west.

The opening of Toga, in Amsterdam in 1971 (it wasn’t raining ‘a’s that day; this is a watermarked image from Alamy)

Europeans started turning up to Japanese restaurants in large numbers only in the 1990s. Right from the start, there was an attempt to sell ‘Japan’ as a whole, with establishments splashing out on bonsai plants, kimonos for staff, Japanese music and paper sliding-doors (shōji).

In London, sushi became yuppie food, after the first kaitenzushi establishments opened in the middle of that decade. Mega-chains Itsu and Yo!Sushi were both founded in 1997, helping to drive the boom onwards and selling American twists on sushi, including the controversial California roll (inside-out sushi, with crab, avocado and cucumber).

By the early twenty-first century, the surf had well and truly struck back. The only fear now, in Japan, was the rise of weird foreign cuisines claiming to be sushi.

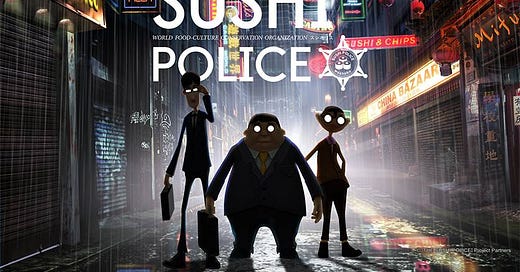

In 2006, a Japanese government ministry went as far as certifying Japanese restaurants abroad, to reassure customers that they knew what they were doing. The initiative swiftly became known as the ‘sushi police’, and was turned into a tongue-in-cheek Japanese anime (2016).

All that remains now is for the sushi police to come knocking on the doors of UK supermarkets, to insist on better-quality sushi for us humble Brits…

—

Suggested Readings:

Katarzyna J. Cwiertka, ‘From Ethnic to Hip: Circuits of Japanese Cuisine in Europe’, Food and Foodways 13 (2005).

Christopher Harding, ‘When the Samurai Came to America,’ Engelsberg Ideas (February 2023).

Eric C. Rath, Oishii: The History of Sushi (Reaktion Books, 2021).

—

Images:

Embassy to the US: Engelsberg Ideas (fair use).

Tokugawa forces: Creative Commons (public domain).

Hōchōnin: Rath, Oishii (fair use).

‘Bowl of Sushi’: Creative Commons (public domain).

Toga: Alamy (fair use).

Sushi Police: SushiPolice.com (fair use).