Part II - the Medieval World - is HERE.

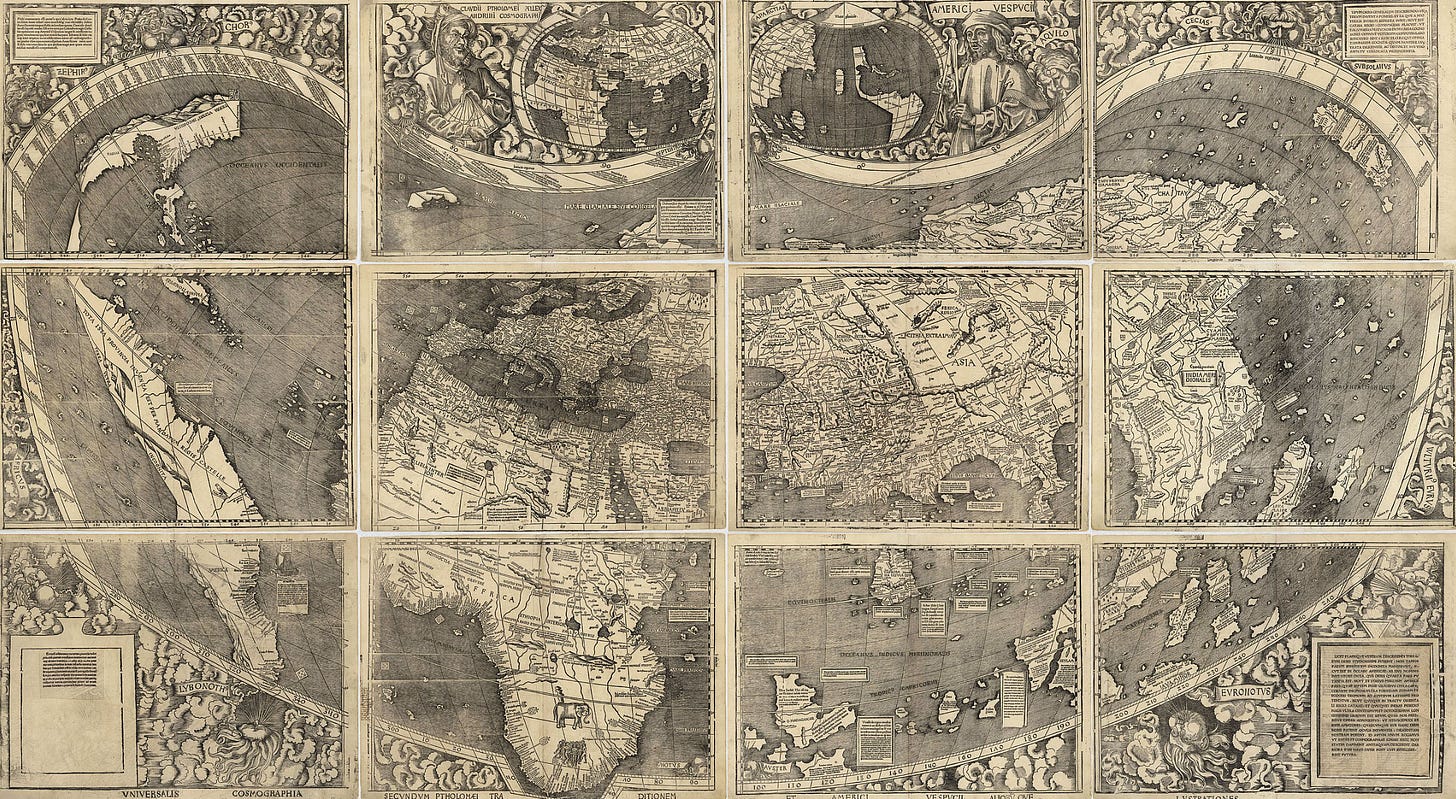

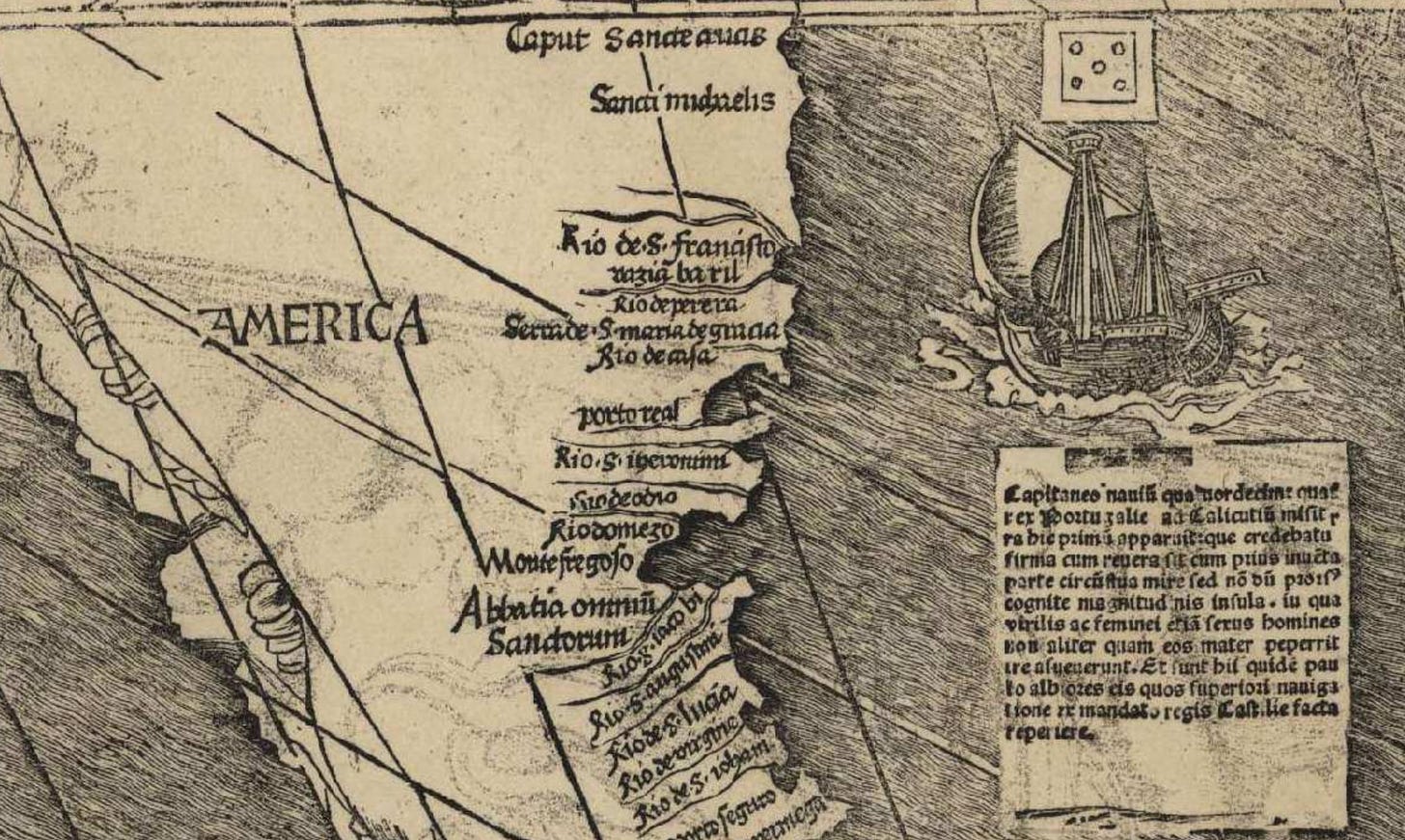

The 1490s ended up being a busy period for cartographers in Europe. Had Christopher Columbus given up his insistence that he had reached Asia on his travels, they might have inscribed his name on their hurriedly re-drawn maps. Instead they wrote ‘America’, after Columbus’s rival explorer, the Florentine Amerigo Vespucci.

Cartographers had to contend, too, with the thorny politics of who owned what, where newly discovered territories were concerned. Since as far back as the fifth century, the leaders of western Christendom had insisted on their right and duty to work for a universal Christian commonwealth. This meant that if the inhabitants of far-off lands violated ‘natural law’ they could legitimately be ejected from those lands. At the same time, early sixteenth-century Catholic powers like Spain and Portugal found that they could claim rights to newly-discovered lands by promising to support missionary work there.

Above: a map made in 1507 shows early impressions of the New World

Below: detail from the bottom left-hand corner of the map shows the first known use of the word ‘America’ on a map

Columbus’ journey westward and Vasco da Gama’s voyage eastward - around Africa’s southern tip and out into the Indian Ocean – gave rise to discussions between Spain and Portugal about how to divide the global spoils. The results took the form of a Papal Bull in 1493, modified by a Treaty of Tordesillas in 1494. A meridian line was drawn down the Atlantic, approximately halfway between the Cape Verde Islands off the west coast of Africa and the lands discovered (and yet denied) by Columbus.

The Spanish took everything to the west: much of the Atlantic, all of the ‘Americas’, a new ocean beyond – christened ‘the Pacific’ in 1520, for its preternaturally calm waters – and finally the Philippines, which were named after the Spanish King Philip II.

The Portuguese received everything eastward of that line as their area of legitimate operation: Africa and Asia, basically, alongside eastern Brazil – of whose existence, jutting out into the Atlantic past the meridian, the Iberian powers had been unaware at the time that Tordesillas was signed (some claim that the Portuguese did know of it, but kept quiet in their own interests).

Dividing the spoils: the Treaty of Tordesillas (1494) and Zaragoza (1529). The latter defined an antimeridian in Asia, following the first circumnavigation of the globe in 1519 – 22. Major sea routes used by Europe’s two great maritime powers are also shown.

What did Asia do for the Portuguese? First and foremost: spices. For a brief moment in 1499, pepper retailed in Venice at around 80 ducats per hundredweight. The same quantity, the Portuguese discovered, could be bought in the Indian coastal town of Calicut for just 3 ducats. Extraordinary profit margins across a range of goods soon turned the Portuguese capital of Lisbon into a major spice market.

As the Portuguese won for themselves a series of bases around the Indian Ocean – in some cases with considerable violence – their vessels began to double as a taxi service for missionaries heading out to Asia. Most influential amongst them was the Society of Jesus (or Jesuits), founded in 1540 and soon acquiring the nickname ‘God’s marines’ for their pledge of loyalty to the Pope.

For the Jesuits, and for the Catholic Church, the answer to the question ‘What might Asia do for us?’ came in three parts: making converts, seeking out allies amongst Asia’s rulers, and demonstrating to Protestant rivals in Europe that the Catholic Church was the one and only legitimate heir to Jesus Christ’s command to ‘go and make disciples of all nations.’

By the turn of the seventeenth century, this venture appeared to be going very well in Japan and very badly in China. Portuguese merchants discovered a lucrative side-trade in the latter half of the 1500s: ferrying goods between China and Japan – who no longer traded directly with one another, after arguments over piracy – and between East Asia, India and Europe.

Silk was a major part of this trade, thanks to the juicy mark-up at which raw Chinese silk could be sold in Japan. At the same time, Japanese products began to find their way back to Europe, from heat-resistant lacquerware to writing desks fashioned from exotic woods and inlaid with silver, mother-of-pearl and tortoise shell.

A Japanese folding screen, c. 1620 – 40, showing Portuguese merchants arriving in the port town of Nagasaki

Japan was divided, in this era, into warring states controlled by feudal lords, many of whom were keen to support lucrative, taxable trade in their domains. Missionaries soon found that by holding out the prospect of persuading their merchant compatriots to favour this or that Japanese port, they could win themselves a warm welcome amongst local lords.

Francis Xavier was amongst the early missionaries to evangelise in Japan, and he found that the work did always go smoothly. Buddhist monks initially thought that he was offering a new form of the Buddha’s teachings, after Xavier introduced himself as arriving from India (which indeed he had: the Portuguese enclave of Goa). Meanwhile, some of the lords with whom Xavier and his colleagues were granted audiences regarded their humble dress not as a sign of admirable humility – as it was viewed back in Europe – but as an insult. Why, wondered these powerful men, had these foreign visitors not bothered to dress properly for such a grand occasion?

Nevertheless, by the 1580s Christianity was doing well enough in Japan that an embassy of four young Japanese Christians – all from important families – was dispatched to Europe on a short tour. They met the Spanish King Philip II and then Pope Gregory XIII in Rome, the latter visibly moved to see Asia starting to make its way into the Catholic fold.

The Japanese embassy meets Pope Gregory XIII in 1585

All this left Jesuit missionaries at the Portuguese base of Macau in southern China feeling a little bit inadequate. Portuguese merchants were regarded in China as a new species of pirate, and missionaries were scarcely more welcome.

It was not until the early 1600s that the Jesuits began to enjoy a little success in China. The secret, amongst the country’s literati elite as amongst India’s high-status Brahmins, was simple: show some respect for the civilization that you are encountering.

In China, the name Matteo Ricci became synonymous with this strategy. He learned Chinese, adopted the style of the literati – silk robes; hair and beard cut in the appropriate fashion - and took a serious interest in Confucianism. Some high-profile converts were duly won and Ricci was tolerated at the imperial court in Peking, though he never met the Emperor.

An early seventeenth-century portrait of Ricci in his Chinese-style clothes

Jesuits like Ricci ended up becoming the first real conduits for Asian wisdom to the West. Part of their missionary strategy was to convert the elites of the countries in which they worked, from the Mughal Emperor in India to his counterpart in Peking. You could not do that without understanding their ideas and beliefs about the world.

That meant understanding something of Islam and Sanskrit sacred literature in India, Confucian ethics and governance in China, and Buddhism in Japan. In Japan, especially, it also meant behaving well enough not to upset the locals – eating with chopsticks and taking care of one’s personal hygiene.

The result of all this, slowly but surely across the 1600s and into the 1700s, was that answers to the question of what Asia can do for Europe began to change. Making money and converts continued to loom large. But interest began to develop, too, in the way that various Asian societies were run, and the things that people believed about the world. The more that Europe questioned itself, across decades of bloody warfare, the more that some of its leading thinkers began to look to Asia and ask not just ‘What can we take?’ but ‘What can we learn?’

Part IV - the Modern World - is HERE.

Suggested Reading:

Robert Eric Frykenberg, Christianity in India: From Beginnings to the Present (Oxford University Press, 2008)

John W. O’Malley et al (eds), The Jesuits: Cultures, Sciences and the Arts, 1540 – 1773 (University of Toronto Press, 1999)

Jonathan D. Spence, The Chan’s Great Continent: China in Western Minds (W.W. Norton & Company, 1999)

David Mungello, The Great Encounter of China and the West, 1500 – 1800 (Rowman & Littlefield, 1999)

Alexandra Curvelo & Angelo Cattaneo (eds), Interactions Between Rivals: The Christian Mission and Buddhist Sects in Japan (c. 1549 – c. 1647) (Peter Lang, 2021)

—

Images:

1507 map: Creative Commons (public domain)

Map of Spanish versus Portuguese global interests: VividMaps (fair use)

Japanese folding screen: Google Arts and Culture (fair use)

The Japanese embassy to Europe: Creative Commons (public domain)

Matteo Ricci in Chinese robes: Creative Commons (public domain)