I’ll be back to my essay series on true stories very soon, but I recently wrote a piece for UnHerd about the emerging phenomenon of ‘Wild Christianity’. I thought I’d post a slightly longer version here - enjoy!

It has become customary, whenever a ‘Christianity is doomed’ news story does the rounds, to find broadsheet commentators mourning the closure of churches, the fading of values and the ebbing of community feeling – without expressing much enthusiasm for the religious vision that they assume once underpinned all this.

What we need, they never quite say, is a service class to perform the embarrassing work of religious belief on our behalf. That way, the better-educated can enjoy our secular outlook in congenial surroundings: the chiming of church bells; the smiles of passers-by who really do think that on some grand cosmic scale we’re all in this together.

The village of Snowshill, in the Cotswolds.

Perhaps I’m being unfair. But was there ever a time when Christian Britain was one big, cuddly Richard Curtis film? When no-one in the pews was there on sufferance, doubtful about or disturbed by what they were hearing and yet compelled to be there by family, neighbours or employers – that famous ‘community feeling’ in action?

This sort of ‘cultural Christianity’ feels like the successor ideology to the New Atheism of the noughties and early 2010s, prone to different but nonetheless serious flaws. New Atheism became caught up in what the Scottish theologian John Macquarrie called a ‘narrow empiricism’. We confine our idea of valid knowledge to that which is verifiable by sense-experience, while intuition, emotion and imagination are relegated to the role of window-dressing. If New Atheism mistook Christianity for a scientific theory, cultural Christianity mistakes it for an identity.

And yet Richard Dawkins was surely onto something when he sought to shake religious traditions by their metaphorical lapels and demand that they explain what exactly they are doing when they use religious language: history, proto-science, poetry – something else entirely? For all that Christian commentators enjoyed depicting the likes of Dawkins as wading out into deep theological waters and promptly drowning, this basic question was manifestly a good one – on which there has long been disagreement amongst Christians of varying stripes.

This is part of what intrigues me about Paul Kingsnorth and Martin Shaw’s conversions to Orthodox Christianity, in both cases via paths that ran through the natural world – Kingsnorth as an environmentalist and one-time Wicca priest, Shaw as a wilderness vigil guide. In essays, podcasts and public appearances – occasionally together: they are friends – the two men are feeling their way towards what they call a ‘wild Christianity’.

Martin Shaw and Paul Kingsnorth.

Both are writers, and know a thing or two about words and how they are used. They are keeping things theologically modest for now – they see themselves as being at the start of uncertain journeys – but I am looking forward to seeing whether this becomes a new turn in our relationship with religion.

Somewhere near the heart of wild Christianity appears to be a powerful sense of numinous presence, within nature and within the Orthodox liturgy, which is at once compelling and strange. Compelling because for Kingsnorth, the idea of a truth to which he could surrender resonated with him very deeply in the run-up to his conversion.

The same holds for Shaw, who as a mythologist appreciates the difference between crafting one’s own life-story and experiencing oneself as a character in a much greater one. ‘It’s not enough to say we are just meaning-making creatures,’ he writes. ‘I think there’s a ground of meaning so profound we can barely face it. That there’s actually more meaning than we can stand.’

The strangeness of this presence is hinted at in Kingsnorth’s reluctance to say much about his conversion – ‘I can’t explain any of it, and it is best that I do not try’ – and in the way that Shaw talks about Yeshua (Jesus): ‘I will meet you in the dark, Yeshua, and I am scared and I am small… I will reach out for your fur in the black.’ For Shaw, the majesty and ‘wyrd-ness’ of Creation, as an authored work, seems to serve as a gauntlet thrown down before the Christian God:

I am looking for a Christianity as huge as this forest. As magnificent as the stars that swirl over it every night. As endless as the River Dart I hear rushing past.

Dartmoor is Shaw’s natural habitat.

In an age of endless cultural recycling – more obvious with social media, but clearly pre-dating it – the two men are calling for the cultivation of an attentive silence, in natural surrounds. We have all but lost this ability to listen, argue Kingsnorth and Shaw, but we can re-learn with the help of others: the medieval saints of Ireland, where Kingsnorth now lives, alongside cultures around the world who understand the value of what Shaw calls ‘putting your great and ancient ear to the dark soil of circumstance and listening’.

We humans, says Shaw, have long been ‘awfully good at picking up the news’ in this way, and turning it into ‘myth’: a ‘heavenly braille’ that stands ‘solid in divine ground’. Kingsnorth seems to agree, calling for a regrowing of our roots and the reestablishment of the ‘vertical plane of life’: tradition, religion, devotion.

That may sound a little like cultural Christianity, but Kingsnorth is more radical than that. He sees western Christianity as helping to give rise to what he calls the Machine: a ‘nexus of power, wealth, ideology and technology’, emerging from the marriage of a human desire for control with modern commerce and a reductive scientific naturalism. Wild Christianity appears to be setting itself up against older juridical, bureaucratic forms of the faith.

In this, and other respects, Kingsnorth reminds me of an English Benedictine monk by the name of Bede Griffiths (1906 – 1993). His attempt to revitalise western Christianity, alongside that of the English philosopher and counter-culture guru Alan Watts, who died fifty years ago this month, turned on the question of how language and inner experience shape one another. I suspect that this may end up being true, too, for wild Christianity.

The (very) young Alan Watts.

As a boy, religious language left Watts terrified:

Take me, when I die, to heaven,

Happy there with thee to dwell…

How sweet to rest

Forever on my Saviour’s breast.

Taken literally, these prayers were baffling and creepy. And yet although Watts’ mother taught them to him at bath-time, she never showed him how they might be understood. Watts tasted life’s magic elsewhere: in the beauty and fecundity of the family garden – tomatoes and raspberries hanging off vines like ‘glowing, luscious jewels’ – and later in East Asian landscape painting, Zen Buddhism, and yoga.

Griffiths, too, was drawn in by nature – in his case, a numinous experience one evening on the school playing fields, set off by the sound of birdsong:

Everything… grew still as the sunset faded and the veil of dusk began to cover the earth… I felt inclined to kneel on the ground, as though I had been standing in the presence of an angel.

Watts and Griffiths regarded the general drabness of mid-twentieth century Britain as evidence of a fundamental disconnect from life at this deep level: the funereal black suit that Watts’ father wore for work; the ‘boxy, red-brick quiet-desperation homes’ to which Watts saw such men returning home at night.

Unsure what to do about all this, Griffiths and some university friends experimented with living a simple life in a cottage in the Cotswolds village of Eastington: no running water; no technology or literature produced after the seventeenth century; and candlelit debates about whether, if the village blacksmith could somehow craft an X-ray machine, it would be acceptable to use it.

Eastington, in the Cotswolds.

Both men came to see that ventures like these failed to get to the real problem, which was the placing of human beings – and, in particular, a discriminating human intellect – at the heart of reality.

Watts’ discovery of this came one evening in his boarding school dormitory, where frustration at his failed practice of yoga and zazen boiled over and he decided to drop both – at which point, quite unexpectedly, ‘Alan Watts’ got dropped instead.

Anxious little Alan was, he realised, no more than a case of mistaken identity. The real Alan Watts was part of an immeasurably greater and inextinguishable whole. The release was profound, and its memory never left him.

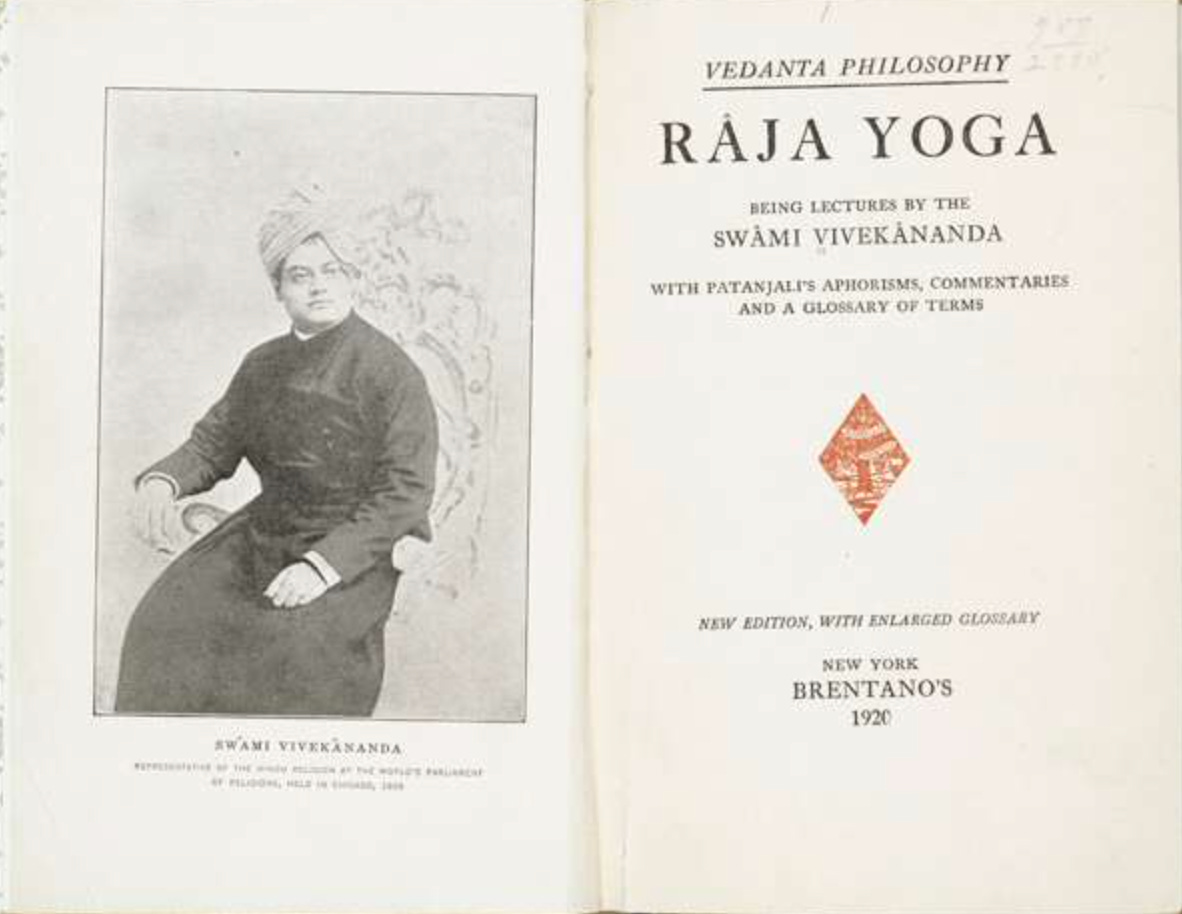

Swami Vivekananda’s Raja Yoga was a major early influence on Watts. He picked up a copy in London’s Camden Market.

Griffiths, having quit the Cotswolds, spent a traumatic night of prayer in Bethnal Green, where he found his still-tentative personal philosophy – Christianity with a dash of Eastern wisdom – completely destroyed, as an ‘abyss’ of darkness and unreason overtook him.

Out on the street next morning, London’s buses appeared to ‘have lost their solidity and [to] be glowing with light.’ God, he concluded, had ‘brought me to my knees, and made me acknowledge my own nothingness . . . out of that knowledge I had been reborn.’

Watts made a name for himself on America’s West Coast in the 1950s and 1960s, as a gifted communicator of Eastern wisdom – to young Americans especially, often on college campuses – and a progressive thinker on everything from psychotherapy to sex and LSD. For a few years before that, however, he served as an Episcopal priest in America’s Midwest.

Looking for a way of describing his experience of that inextinguishable whole in Christian language, Watts suggested that God is ‘personal’ in the sense of being ‘immeasurably alive’. Sadly, he went on, while in India Shiva dances and Krishna plays the flute, Midwestern church-goers appear condemned to sit amidst heavy courthouse furniture – pews and pulpits – apologising to God, ‘asking him not to spank’ them, praising him in formulae, and engaging in enforced folksiness and ‘fake joy’.

The priestly Watts, early 1940s.

An institutionalised pride is at work here, Watts declared. Everyone talks about grace, but in practice most people want to work for their own salvation – and to see it denied to people who don’t put in the hard yards.

This, he thought, gives rise to a narrow notion of ‘meaning’: an earned and – in practice – endlessly deferred happiness. The idea that play might be a more accurate analogy than work, for the divine life and our participation in it as human beings, will, Watts felt sure, strike most congregants as blasphemous. And yet this was what one of his later LSD trips revealed to him: reality as a giant game of hide-and-seek, with the universe playing at being lots of different things and people.

‘Flow’ is another good analogy, thought Watts, as found in Taoist talk of reality as way, breath and water. Western Christianity possesses something strikingly similar in the Holy Spirit, but most Christians prefer to talk about Father and Son, and the debt that human beings owe to both.

Some of Watts’ ecclesiastical colleagues suspected him of being little more than a pantheist with a gift for semantics. And therein lay the challenge. No doubt Watts’ pioneering church services were lots of fun to attend: conversation and jokes, Gregorian chant and piano improvisations, smoking and drinking, sermons capped at fifteen minutes. But where was Jesus Christ in all of this? And wasn’t Watts’ image of God just a little too convenient: personal enough to be lively, interesting and joyous, but not so personal as to make demands of him or censure his behaviour – his ‘boozing and wenching’, as Watts put it?

Bede Griffiths eventually faced similar questions. Having become a Catholic and a Benedictine in the 1930s, he moved to south India in the mid-1950s and began to pioneer new forms of monasticism and inter-religious dialogue. Over time, he built a strong following amongst westerners, thanks to his writings and his gifts as a spiritual guide.

Bede Griffiths (1906 - 93).

Griffiths ended up developing a deep fondness and respect for Hinduism, and in particular the Upanishads, the Bhagavad Gita and the Advaita Vedanta philosophy. His ecumenical work was widely praised, and seemed well-suited to the post-colonial era. And yet, asked his critics, was this still Christianity?

Watts and Griffiths both approached questions like these by appealing to an elevated notion of ‘myth’: neither tall tale nor proto-science, but rather a story that is somehow spoken by reality itself, composed of symbols that are capable of mediating that reality for ordinary human minds.

Carl Jung, Owen Barfield, J.R.R Tolkien and C.S. Lewis were amongst those offering sophisticated variations on this general theme in the middle decades of the twentieth century. Watts read most of them, but some combination of that first numinous experience, the loss of his career as a minister (and with it the need to grapple so urgently with Christian theology) and his immersion in West Coast counter-culture led him to focus – perhaps rather narrowly – on the liberating potential of myth.

The message across religions was, in the end, the same, thought Watts: ‘You are that!’, as the oft-quoted line from the Upanishads had it: let go of the false sense of being an independent little ‘me’ – at once prideful and anxious – and you will experience your identity with Brahman, or the Ground of Being.

Alan Watts (1915 - 73) in his West Coast era.

Watts was excited by the prospect that quantum physics might offer backing for this understanding. The universe was not some vast, mostly empty arena in which clearly-bounded bits of stuff bounced off one another. Reality at its deepest seemed to comprise events rather than ‘stuff’, with relationships somehow more ‘real’ than individual people and things.

Anticipating the work, in our own day, of the psychiatrist and writer Iain McGilchrist, Watts expressed confidence that people could see this for themselves by exchanging the ‘spotlight vision’ of everyday, discriminating awareness for a more immediate, intuitive and open ‘floodlight’ vision.

Griffiths, for his part, always cautioned against a syncretic approach to religion, on the basis that it risked placing a human being, rather than God, at its centre. He did not, however, understand his own religious experience in exclusively Christian terms. His inner experience resonated in a compelling, all-but-inescapable way with Christian scripture, and with John’s gospel in particular. But he found that something similar occurred with Hindu scriptures.

There could be no getting round the back of these experiences, to compare them with one another. Alternative forms of knowledge – history, the sciences – might nuance the general picture, helping to set the boundaries of what was plausible. But they weren’t equipped to compete at depth with religious language and intuition.

This, perhaps, is what it means for a story to be given rather than created by human beings. You pick up its contours as best you can – Griffiths defined faith as ‘utter receptivity to the divine’ – without presuming to understand its origins. As David Bentley-Hart - like Shaw and Kingsnorth, a convert to Orthodoxy - puts it: ‘not what it is, but that it is’. If we allow ourselves to appreciate the sheer gratuity of this, it will be more than enough.

Alan Watts’ fanbase seems to renew itself in every generation. Where once they thumbed through his paperbacks on the hippie trail, now they have podcasts and YouTube videos of his talks. Read the comments underneath those videos, and liberation remains the key to his appeal: from a false and painful self-understanding, and from the wider culture to which that understanding keeps on giving rise – decade after decade.

An Alan Watts animated by the creators of South Park.

There is much here that might contribute to a ‘wild’ Christianity: Watts’ warnings about safe, nostalgic religion as a kind of collective clinging; his intuition of a God who is ‘immeasurably alive’; his self-confessed ‘rascality’.

And yet I’m not sure that liberation by itself is enough. Don’t we soon find ourselves back where we were, and in need of liberation once again? Griffiths thought that real liberation is a matter of attentive, committed listening, moving step by step according to what you hear as you go. A Christianity built on that, and capable of generating community from it, is a wild idea indeed.

Thank you for reading!

If you’re more or less glad that you did, a little heart click would be much appreciated - at the top or bottom of the post, depending on where you’re reading this.

If you really liked it, please consider subscribing and/or sharing this post. IlluminAsia is just getting started, and votes of confidence early on mean the world.

—

Images:

Snowshill: House & Garden (fair use).

Martin Shaw and Paul Kingsnorth: Instagram (fair use).

Dartmoor: BBC (fair use).

A young Alan Watts: AlanWatts.org (fair use).

Eastington: Sykes Holiday Cottages (fair use).

Raja Yoga: Creative Commons (public domain).

The priestly Watts: AlanWatts.org (fair use).

Bede Griffiths: DominicCogan.com (fair use).

West Coast Watts: The Marginalian (fair use).